Funny thing about Vincent Van Gogh‘s series of sunflower paintings. As a subject, they’re as synonymous with the artist as any could be. His self-portraits and his visions of starry nights are iconic, of course; when it comes to still-life, though, when one thinks of Van Gogh, one thinks of sunflowers.

Funny thing about Vincent Van Gogh‘s series of sunflower paintings. As a subject, they’re as synonymous with the artist as any could be. His self-portraits and his visions of starry nights are iconic, of course; when it comes to still-life, though, when one thinks of Van Gogh, one thinks of sunflowers.

But they nearly didn’t happen. He began painting sunflowers in earnest, in August, 1888. He’d planned on painting from life that week but fate intervened, by way of some models who simply didn’t show up on time. Struck by the muse and eager to put pigment to canvas, Van Gogh cut some locally grown sunflowers, arranged them in a terra-cotta vase, and began to work. Within five days he’d completed four still-life paintings. They’d go on to rank among the most eminent and valuable paintings in existence.

Alas, they’re not all still existent. One hangs today in London’s National Gallery. Another is at the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich. A third disappeared into a private collection sometime in the late 1940s, and hasn’t been seen since.

And the fourth? A tragedy. Now known as the Missing Sunflowers, it was owned by wealthy Japanese businessman Koyata Yamamoto, whose home was obliterated by American bombers on August 6th, 1945—the same day that Hiroshima was destroyed by the atomic bomb. The story goes that Yamamoto nearly saved the painting, but encased in its bulky frame (which was actually handcrafted by Van Gogh) it was too heavy. He left it behind to burn.

Yamamoto’s Van Gogh is gone forever. But now, 70 years later, we can finally get a look at it. Art historian Martin Bailey, while researching a new book on the sunflower series, unearthed a previously unknown color photograph of the lost painting, presumably taken in Japan, sometime in the 1920s. Amazingly, the picture includes striking detail of Van Gogh’s timber framing, which he painted a burnt orange to match the sunflowers. This was a significant departure from convention, which at the time dictated that picture frames should be gilt or white, nothing else. Like so many others it was a convention that Van Gogh chose to ignore. Since all his other custom framing is thought to be lost, this is our first visual record of the artist’s attention to presentation.

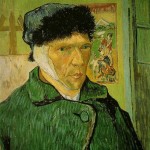

Even modest success was denied to Van Gogh in his lifetime, and within two years of the painting of the sunflowers he’d be dead. The massive, near-universal acclaim his work received after he was gone is out of proportion, if we’re being honest, to his talent, style, and techniques—impressive though they may be.

No, part of Van Gogh’s appeal has to be the tragedy and misery that seem so integral to his life. We imagine we can see his pain in every brush stroke.

In the best of worlds, though, tragedy is merely prelude to redemption. It’s the path one takes toward greater things.

Vincent Van Gogh never completed that journey. He got lost on the way. The same can be said, in a way, for his lost sunflowers. The painting lived but briefly then was turned to ashes.

But now against all odds it’s before our eyes once again. It’s not resurrected, but still we’ve gleaned a glimpse of it. It’s a reflection of redemption—not much, but the best we could have hoped for.

Vincent Van Gogh had no such hope, which is why he died mutilated, insane, alone. There was a symbolic inferno inside him, every bit as real as the flames that consumed his sunflowers. The tragic irony is that without it, his name might be unknown today, and his sunflowers might have never gone to Japan.