Impressionism is arguably the most influential artistic movement of the last half millennium. It represented a stylistic break with the rigid Realism that preceded it, and inspired in its wake not only the techniques and subject matter embraced by visual artists, but also the writers, musicians, and philosophers who’ve shaped our modern culture. A textbook definition of Impressionist painting might speak of abbreviated brush-strokes and the unblended use of color to capture fleeting conditions of light and atmosphere—and it would be correct in doing so. But in broader, and maybe much more accurate terms, Impressionism is nothing more or less than a worldview. It’s a way of describing what the eye sees and the heart feels, denying the simultaneous tugs of jadedness and exuberance, and opting instead for the middle road of studied attention.

Impressionism is arguably the most influential artistic movement of the last half millennium. It represented a stylistic break with the rigid Realism that preceded it, and inspired in its wake not only the techniques and subject matter embraced by visual artists, but also the writers, musicians, and philosophers who’ve shaped our modern culture. A textbook definition of Impressionist painting might speak of abbreviated brush-strokes and the unblended use of color to capture fleeting conditions of light and atmosphere—and it would be correct in doing so. But in broader, and maybe much more accurate terms, Impressionism is nothing more or less than a worldview. It’s a way of describing what the eye sees and the heart feels, denying the simultaneous tugs of jadedness and exuberance, and opting instead for the middle road of studied attention.

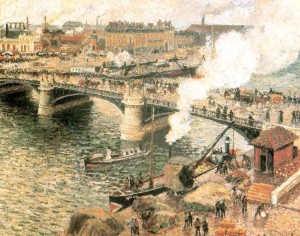

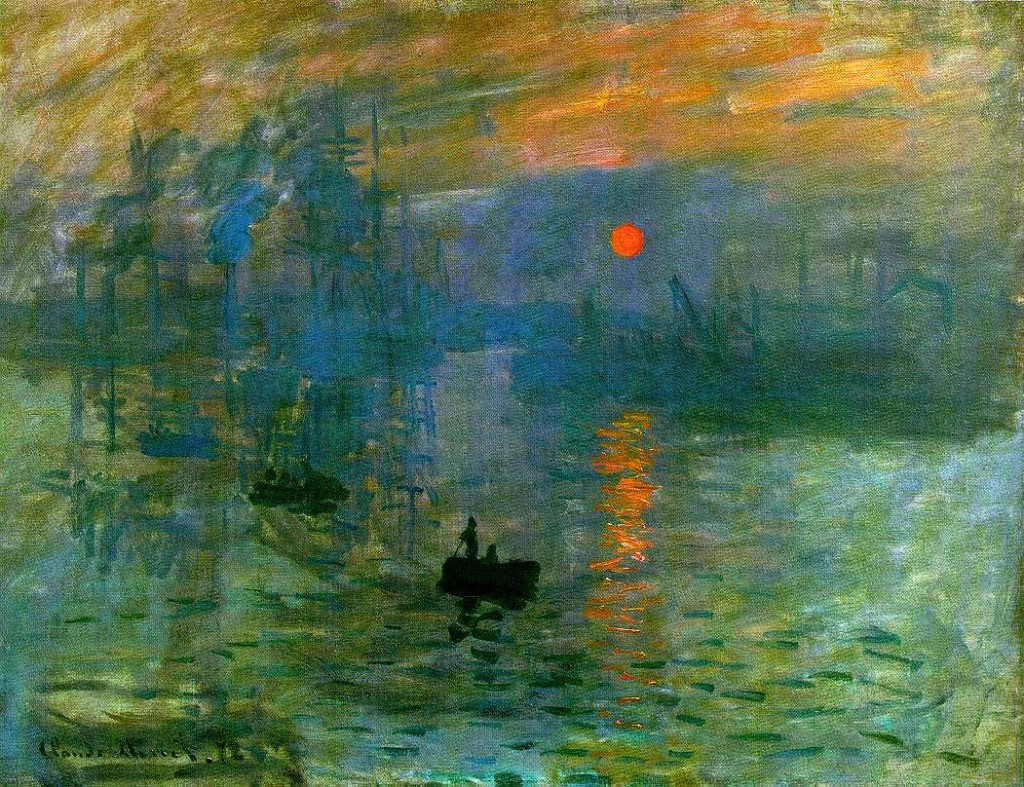

Given that perspective, it’s worthwhile to wonder how such a dramatic movement came into being. There are plenty of answers to that, of course, all of them tackling the question in different ways. We’d be equally factual in saying that Impressionism could only have been created in France in the 1870s, when the availability of rail transport, portable easels, and mass-produced oil paints opened the countryside to previously studio-bound Parisian artists—and that Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Degas, specifically, created Impressionism with a single, significant exhibition held in 1874—and that Monet, singularly, gave both impetus and a name to the movement with his 1872 painting, Impression, Sunrise (Impression, Soleil Levant), seen above.

On that last account, we’ve now been given fascinating pinpoint accuracy. Working from the not unreasonable assumption that Monet painted what he saw, astrophysicist Don Olsen pored over clues in Monet’s brushwork to identify a moment in time that inspired an artist, who in turn inspired an artistic revolution.

Olsen’s methodology is captivating, and is worth exploring in detail. Here’s the Cliff’s Notes version: He began by determining Monet’s vantage point: a third-floor balcony at the Hotel d’Amirauté au Havre. The view is easterly, confirming that the sun is on the rise, and by calculating its position (no more than three degrees above the horizon) he knew that the scene must have occurred twenty to thirty minutes after sunrise.

From there he delved into minutia: the tide, the sea level, the condition of fog, even the wind direction as indicated by plumes of smoke in the distance. Each factor, paired with historical weather reports and documented characteristics of La Havre harbor, narrowed the date. Until he had an answer.

Monet saw that sunrise, was impressed by it, at 7:35 am on November 13th, 1872.

Maybe it’s an academic exercise at best, calculating that. Maybe it’s trivial at best knowing it. But knowing also that Impressionism begat Post-Impressionism, then Cubism and Modernism, and made way for giants like Van Gogh and Picasso, Pollock and Lichtenstein, and indeed the universe of contemporary art and artists that serve us today…then maybe we can agree it’s constructive to publish a birth certificate for Impressionism, one that registers the moment of delivery. That’s what Don Olsen has provided.

Or maybe it’s irrelevant. Maybe all we need do with Impressionism is all we need do with all great art: Just experience it, and be awed….