He was the greatest. He told us so, but he really didn’t need to. His greatness was easily seen, perfectly understood.

He was the greatest. He told us so, but he really didn’t need to. His greatness was easily seen, perfectly understood.

When he was 12 years old, in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, his bicycle was stolen. Young Cassius Clay, as he was then named, told police officer Joe Martin that he would find and thrash the thief. Martin, who was also a boxing coach, told the youngster that he’d need to learn to fight first. And with Martin’s help, he did.

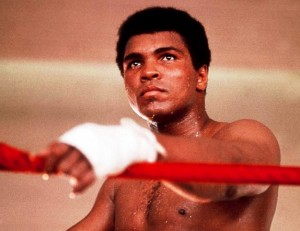

What makes a great boxer? There has to be more, some X factor, beyond the speed, strength, agility, stamina, and technique that are required just to survive in the ring. Whatever it was, Ali had it. Within six years of the start of his amateur career, he’d won more than 100 bouts, won numerous Golden Gloves, and captured gold at the 1960 Rome Olympics.

His professional career began soon after, which brought worldwide, lifetime fame, and a series of ups and downs that would also last a lifetime. In the run-up to his first title fight, against Sonny Liston in 1964, Ali achieved pop-culture immortality when he promised to “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” He also explained away his boasting with a simple, prophetic, and unarguable truth: “It’s not bragging if you can back it up.” He beat Liston in seven rounds and became the heavyweight champion of the world.

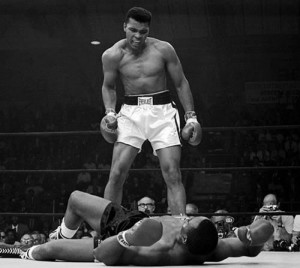

In the run-up to his first title fight, against Sonny Liston in 1964, Ali achieved pop-culture immortality when he promised to “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” He also explained away his boasting with a simple, prophetic, and unarguable truth: “It’s not bragging if you can back it up.” He beat Liston in seven rounds and became the heavyweight champion of the world.

It was Cassius Clay who won that fight, but it was Muhammad Ali who announced, just weeks later, that he’d become a Muslim and had joined the Nation of Islam. His popularity ebbed. And it hit a nadir a year and a half later when he refused a draft summons, declared himself a conscientious objector, and famously said “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” He was stripped of his title and banned by the World Boxing Association, and indicted as a draft dodger by the Justice Department.

But he was The Greatest. He had that X factor, that force of personality, and these too would be fights he’d win. In 1970 he succeeded in getting his boxing suspensions overturned. In 1971 the U.S. Supreme Court vacated his criminal case. In March of that year he lost a 15-round decision to heavyweight champ Joe Frazier. He fought rematches with Frazier in 1974 and 1975 (the Thrilla in Manila) and won both.

Then George Foreman. Then Leon Spinks, Then Larry Holmes. From the seventies into the eighties, Muhammad Ali kept fighting. He was visibly slowing, wasn’t winning as consistently, but he was still The Greatest. He was perhaps the best known sportsman on the planet. He remained cocky, but he was never unkind. He was quietly philanthropic, extraordinarily open and approachable to his fans. By now a Sunni Muslim, he didn’t talk much about his faith, other than to encourage peace and inclusiveness

In 1984 Muhammad Ali, age 42, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome, a degenerative neurological disorder similar in impact to Parkinson’s disease. Its effects were glaring, heartbreaking. Ali was retired by now, much less in the limelight, but he didn’t hide away. He’d still grant interviews, speaking slowly and  carefully, with tremors wracking his body. His mind remained strong, he still had much to say, and far from being shamed by his condition, he seemed content to share it, for the sake of understanding.

carefully, with tremors wracking his body. His mind remained strong, he still had much to say, and far from being shamed by his condition, he seemed content to share it, for the sake of understanding.

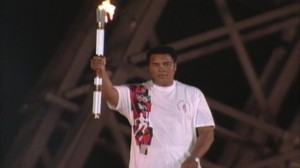

In the coming years, rumors of his declining health abounded. So, in his inimitable style, he surprised us all in 1996, at the opening ceremonies of the summer Olympics in Atlanta, by appearing with torch in hand. He slowly made his way through the hushed stadium and lit the Olympic flame. He’d reprise his surprise role in 2012, in the London games, presiding over the Olympic flag ceremony.

Muhammad Ali’s health issues have persisted so long, and he bore them so well, that I suppose we all were in silent agreement that the champ was winning, that The Greatest had rope-a-doped Parkinson’s. Would that were true. A series of systemic infections weakened him over the last twelve months or so. In the last few weeks he developed difficulty breathing. Two days ago he was unconscious, and breathing with a respirator.

Last night The Greatest passed away in a Phoenix hospital, not far from the Muhammad Ali Parkinson’s Center. May he have gone gently with the knowledge of how much he meant to us, and may he rest in peace.