Knowing who’s who in your major 20th century art movements may have netted you, well, very little up until now (save self-satisfaction or smugness, in alignment with your virtues). But if you’ve got a grasp of the cast of characters—including a particular infamous alias–of the dramatic absurdist movement that flowered almost exactly a century ago, then you might find that knowledge taking you places…

Knowing who’s who in your major 20th century art movements may have netted you, well, very little up until now (save self-satisfaction or smugness, in alignment with your virtues). But if you’ve got a grasp of the cast of characters—including a particular infamous alias–of the dramatic absurdist movement that flowered almost exactly a century ago, then you might find that knowledge taking you places…

…for at least one day only; tomorrow, Sunday April 9th.

Should the morrow find you in Philadelphia, Beijing, Berlin, Amsterdam, or Paris, you can earn yourself free admission to fine art museums in any of those cities (including Philly’s Museum of Art, home to the largest collection of work by seminal Dadaist Marcel Duchamp), simply by speaking the password.

Dada as an art revolution was triggered by the same catalyst as a host of other early 20th century revolutions: World War I. It was a reaction in real time to the war, growing into life with the artists amidst the refugees and the wounded, the first ones back from the front. Before the carnage of the Somme, before the Eastern Front collapsed or the Yanks came over, a few dazed creators escaped to relative European safety, or across the seas to New York. And there they proclaimed the absurdity of it all.

the seas to New York. And there they proclaimed the absurdity of it all.

Duchamp left for New York before the title Dada itself was generally agreed upon (it  means “yes yes” in a couple languages, and refers to something similar to ‘hobby horse” in others–as an art descriptor it’s essentially and intentionally meaningless). But the spirit of Dadaism was already contrived and intact, and it was with Marcel Duchamp.

means “yes yes” in a couple languages, and refers to something similar to ‘hobby horse” in others–as an art descriptor it’s essentially and intentionally meaningless). But the spirit of Dadaism was already contrived and intact, and it was with Marcel Duchamp.

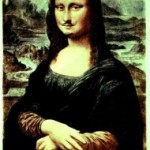

One hundred years ago Duchamp assumed an alias, and scribbled it upon the porcelain of an upturned urinal. He called it sculpture and named it Fountain. On April 9th, 1917 Fountain was rejected for entry in the First Annual Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. That was the day that the art establishment met Dada, and was not smitten.

A century on and we may or may not yet be smitten by a urinal-as-sculpture. But I think we at least better understand the message. We honor it by realizing that for a hundred years, Dada has been saying something urgent and eternally relevant, and saying it in a bizarre enough fashion to plow through every psychic filter we try to throw in front of it.

So it’s entirely fitting that you join in the absurd, in Beijing and Paris and the other places, by whispering a shibboleth at a docent in lieu of admission, in the form of a name of a man who never was—he who signed the urinal and was rejected into legend: “Richard Mutt.”