Nearly five hundred years after his death, Leonardo Da Vinci is still celebrated, and widely recognized, as one of the Western world’s most accomplished polymaths, inventors, and above all, artists. Even the most uninitiated can easily see why—a glance through his notebooks reveal an uncommon and deeply penetrating

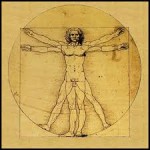

Nearly five hundred years after his death, Leonardo Da Vinci is still celebrated, and widely recognized, as one of the Western world’s most accomplished polymaths, inventors, and above all, artists. Even the most uninitiated can easily see why—a glance through his notebooks reveal an uncommon and deeply penetrating  mind at work. The sketches of his inventions demonstrate a grasp of mechanics and dynamics far ahead of his era. And his art? It’s not just the beauty of his work, although that’s evident in abundance. It’s the technical precision, the startling fidelity of his capture of his subjects, almost mystical in the execution. In reality it was simply because he was very, very good at his craft; he understood light, he understood perspective, he understood motion…and he excelled at distilling these things through pigment, onto surfaces.

mind at work. The sketches of his inventions demonstrate a grasp of mechanics and dynamics far ahead of his era. And his art? It’s not just the beauty of his work, although that’s evident in abundance. It’s the technical precision, the startling fidelity of his capture of his subjects, almost mystical in the execution. In reality it was simply because he was very, very good at his craft; he understood light, he understood perspective, he understood motion…and he excelled at distilling these things through pigment, onto surfaces.

As to exactly how he did that—well, lacking the opportunity to look over the genius’s shoulder and watch him work, the best we can do is to study his paintings, and ever so gently, deconstruct them. And in that respect, a major discovery has just been made.

Leonardo’s circa-1480s painting Lady with an Ermine, is perhaps his second most famous portrait. Like the Mona Lisa the renown partially arises from embedded mystery: enigmatic elements, and even controversy as to the identity of the subject.

Although the matter is far from settled, the woman in the Ermine painting is widely assumed to be Cecilia Gallerani, mistress to Duke Ludovico Sforza of Milan. Perhaps the most compelling evidence in that regard is that shortly before the portrait is believed to have been commissioned, Sforza was inducted into the heraldic Order of the Ermine by the King of Naples. The prominent inclusion of that strange, sleek animal, then, might have been Leonardo’s less-than-subtle salute to his patron.

It’s long been known that multiple layers of paint—early drafts, essentially—were hidden beneath the Lady with an Ermine. That was revealed by X-ray examination of the portrait decades ago, and similar testing yielded similar results for many Da Vinci paintings. Until now, though, there hasn’t been a noninvasive, non-destructive way of peeling back those layers, and seeing what Leonardo chose to cover up.

Enter, thankfully, LAM (layer amplification method). The technique of exposing surfaces to multiple, sequential wavelengths of intense light, then measuring the reflections, has been employed by engineer Pascal Cotte of Lumiere Technology to unveil not one, but three versions of the Lady with an Ermine portrait. Examining the evolution of the work gives us remarkable insight into how Da Vinci approached his work.

What’s most noticeable is the ermine, and particularly its complete absence in the first, deepest layer. Next came the grey ermine—smaller, more subdued, and much less life-like. If the painting’s subject and provenance are indeed what art historians have concluded, then it’s tempting to suspect that Ludovico Sforza’s insistence might have spurred the inclusion, and finally the refinement, of that haunting little creature.

What’s most noticeable is the ermine, and particularly its complete absence in the first, deepest layer. Next came the grey ermine—smaller, more subdued, and much less life-like. If the painting’s subject and provenance are indeed what art historians have concluded, then it’s tempting to suspect that Ludovico Sforza’s insistence might have spurred the inclusion, and finally the refinement, of that haunting little creature.

It’s also interesting to notice the evolution of the Lady’s attire. If she sat for Leonardo (if, in other words, Leonardo didn’t somehow paint this from memory), then we have an almost exact idea of what she wore that day. But why does the small black bow at her neckline disappear between the first version and the second? Why does a blue cloak appear over her left shoulder, concurrent with the arrival of the ermine? These are relatively tiny questions of detail, historically unanswerable, but so very fascinating to ponder when we consider the process of a master painter at work.

Finally, and very tellingly, notice the Lady’s face. Not a brush-stroke changes there. Of all aspects of Da Vinci’s skill, his grasp of the human form was probably his greatest strength. At first pass he captured the Lady’s likeness; he knew it, and he was intelligent and confident enough to never second guess it.

It’d be trite, and maybe not entirely honest to end by proclaiming that “there will never be another Da Vinci.” Yes, he was a resounding, history-shaking genius…but unto every generation is bestowed not just monsters, tyrants, and legions of the mediocre, but also a far share of geniuses. There will be another Da Vinci, or at least someone of comparable talent and depth. That someone might be in art school right now, or in grade school, or on the streets, spraying masterpieces onto concrete-block walls.

With luck we’ll see that genius at work, in real time or close to it, and get some dim idea of how perfect genius expresses itself. With luck a half-millennium won’t pass, and future admirers won’t be left to look back, and only hypothesize.