It was roughly a hundred years ago (the dates are hard to pin down) that one of history’s most vibrant, innovative, and influential art movements was born. Dadaism dominated the scene for a scant twenty years, spinning off from the fin de siècle Cubism of Picasso and Cezanne, and maturing at last into the Surrealism of Dali and Magritte. Dada was a brief, bright flare; with a brevity perhaps not planned by its progenitors, but certainly in accordance with their common philosophy. As anti-art, Dadaism was pre-programmed for suicide, and if it had resisted that urge it would have necessarily devolved into self-parody.

It was roughly a hundred years ago (the dates are hard to pin down) that one of history’s most vibrant, innovative, and influential art movements was born. Dadaism dominated the scene for a scant twenty years, spinning off from the fin de siècle Cubism of Picasso and Cezanne, and maturing at last into the Surrealism of Dali and Magritte. Dada was a brief, bright flare; with a brevity perhaps not planned by its progenitors, but certainly in accordance with their common philosophy. As anti-art, Dadaism was pre-programmed for suicide, and if it had resisted that urge it would have necessarily devolved into self-parody.

More than anything else, Dadaism was a response to and a child of war. It appeared toward the mid-point of the First World War, as it became globally clear that the conflict was to be no grand adventure, but rather the ruthless culling of a generation. Dadaism was, as a result, peculiarly political, and it’s interesting to note that it first appeared in then-neutral countries, the United States and Switzerland, but its adherents were primarily combat veterans and refugees from the belligerent nations, especially France and Germany. As soon as the war ended those nations, and many others, embraced Dada in a way that can almost be described as a frenzy, with Paris, Berlin, Cologne, and Zurich as the artistic centers of gravity.

Reactionary though it was, Dada had difficulty defining itself, its goals, its ideology. More often than not, in accordance with its nihilistic roots, it was described only in terms of opposition—it was anti-bourgeois, anti-statist, and in terms of art as it was understood in the day, it was anti-art.

Reactionary though it was, Dada had difficulty defining itself, its goals, its ideology. More often than not, in accordance with its nihilistic roots, it was described only in terms of opposition—it was anti-bourgeois, anti-statist, and in terms of art as it was understood in the day, it was anti-art.

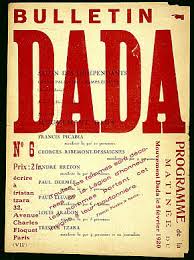

Today, Dada is best remembered as visual art forms—the paintings of Francis Picabia, the “Ready Made” sculptures of Marcel Duchamp, and the collages of Max Ernst. In its day, though, Dada refused such easy categorization, and embraced a universe of expression. Poetry, in particular, was integral to early Dadaism, even if some of its experimental efforts haven’t stood the test of time (Romanian Dadaist Tristan Tzara, for example, pioneered both nonsense verse—rhyming syllables with no inherent meaning, and ‘simultaneous poems’—cacophonous readings by two or more poets at the same time). Photography and film were also important Dadaist media; and all of it, during the Dada heyday of 1915 through 1925, tended to be presented in massive, chaotic, barely planned Dada

the collages of Max Ernst. In its day, though, Dada refused such easy categorization, and embraced a universe of expression. Poetry, in particular, was integral to early Dadaism, even if some of its experimental efforts haven’t stood the test of time (Romanian Dadaist Tristan Tzara, for example, pioneered both nonsense verse—rhyming syllables with no inherent meaning, and ‘simultaneous poems’—cacophonous readings by two or more poets at the same time). Photography and film were also important Dadaist media; and all of it, during the Dada heyday of 1915 through 1925, tended to be presented in massive, chaotic, barely planned Dada happenings, which in of themselves might be thought of as proto-performance art.

happenings, which in of themselves might be thought of as proto-performance art.

The word “Dada” is, naturally enough, part of the absurdist package that formulates the movement’s counter-manifesto. It is essentially, purposely meaningless, yet it hints at meaning. In English-speaking cultures, it’s often a child’s first word. In the Slavic nations, it means “yes, yes.” And in colloquial French, it refers to a hobbyhorse. It is a melange that defies precise definition, much like the art and artists we call Dadaist.

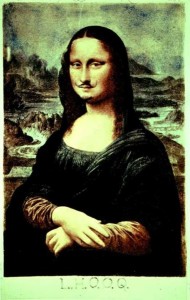

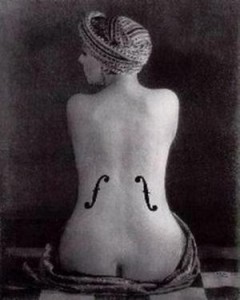

In the United States, where (arguably) Dadaism first expressed itself, the impetus wasn’t just political, it was also an artistic backlash. The American art scene was still coming to grips with the legendary Armory Show of 1913, which all but forced the country to accept the relative new waves of Cubism and Post-Impressionism. Certain artists living and working in New York, like photographer Man Ray and expatriate Frenchman Marcel Duchamp, thought they could bring even more  pressure to bear, by presenting America with art that was avant-garde to the point of folly. Duchamp, for example, turned a urinal upside-down, named it “Fountain,” and called it sculpture. Ray glued tacks to a flatiron and photographed it. Both pieces, simple and absurd constructions, have become iconic Dadaist representations.

pressure to bear, by presenting America with art that was avant-garde to the point of folly. Duchamp, for example, turned a urinal upside-down, named it “Fountain,” and called it sculpture. Ray glued tacks to a flatiron and photographed it. Both pieces, simple and absurd constructions, have become iconic Dadaist representations.

New World Dada was to meet the Zurich-born (whence the name “Dada” was coined) stripe after the war, and like weather-fronts colliding, the amalgam was both creative and destructive. It flourished in this collaborative form for just a few more years before disintegrating. Was it the internal competition, perhaps deep-seated incompatibility, that brought it down? Or was it the lull of peace-time, and a lack of a counterpose to confront and ridicule, that made it irrelevant?

Either way, it was gone, but surely not forgotten. The direct descendants of the Dadaists were the mid-century Surrealists, but the current hardly stopped there. Politically provocative performance art, poetry slams, even punk rock owes a debt to the Dadaists who blazed their trails a century ago.

However Dada died, and in whatever forms its genes live on, its central tenet is as relevant today as it was during the dark days of Verdun: Art needn’t be static and it mustn’t be silent. Art should carry a message, even if that message is a wordless scream of rage and anguish.