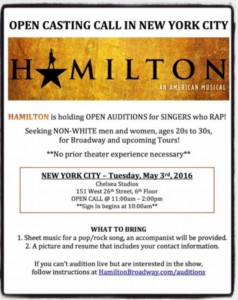

Lin-Manuel Miranda‘s hit Broadway musical stirred up a bit of controversy last week, as a casting call specifying “NON-WHITE” actors drew the ire of a theater union and sparked choruses of ‘reverse-racism.’

Lin-Manuel Miranda‘s hit Broadway musical stirred up a bit of controversy last week, as a casting call specifying “NON-WHITE” actors drew the ire of a theater union and sparked choruses of ‘reverse-racism.’

The verbiage was clumsy, to be sure (and it has since been amended, with producers now saying the auditions will be open to all), but the outcry was a bit overdone, and probably undeserved. In productions of all sorts it’s not at all unusual for the race or ethnicity of characters to be specified prior to and during casting. If the ‘Hamilton’ casting call was guilty of anything, it was a semantics error—had the producers specified that they were seeking actors of color, it probably wouldn’t have drawn any untoward attention at all. Simple phrasing here provided the illusion of exclusion, and a regrettable opportunity for the sort of people who beat their chest over this reverse-racism nonsense every chance they get.

The verbiage was clumsy, to be sure (and it has since been amended, with producers now saying the auditions will be open to all), but the outcry was a bit overdone, and probably undeserved. In productions of all sorts it’s not at all unusual for the race or ethnicity of characters to be specified prior to and during casting. If the ‘Hamilton’ casting call was guilty of anything, it was a semantics error—had the producers specified that they were seeking actors of color, it probably wouldn’t have drawn any untoward attention at all. Simple phrasing here provided the illusion of exclusion, and a regrettable opportunity for the sort of people who beat their chest over this reverse-racism nonsense every chance they get.

Which is a shame, because by all accounts ‘Hamilton’ is a transcendent play. I haven’t seen it yet but I very much want to. I will, as soon as I can. Broadway musicals tend not to be my thing, but from everything I’ve seen and heard, ‘Hamilton’ is in a class by itself.

Race, I think, is central to the production, but not at all in a negative way. The visual device of casting black and brown actors in the roles of historical white men and women is as effective and uplifting as the aural device of telling their stories in rhyme, rap, and hip-hop. There are many levels to this fascinating and unexpected juxtaposition—it’s not as simple as blending the past and the present, of telling an 18th-century story in a 21st-century voice.

Americans are encouraged, sometimes strong-armed, into idolizing their founding fathers. There’s much in the USA’s origin story to celebrate, but let’s be honest—it’s much easier to revere Revere and Washington and Jefferson when you share their European ancestry. We’ve somewhat failed the hundred million or so of our fellow citizens who don’t fall into that category, by giving them little common ground in which to connect with the people who created America.

‘Hamilton’ represents an effort by Lin-Manuel Miranda and others to create that common ground themselves. Miranda found in the inspiring yet tragic story of Alexander Hamilton something he recognized, something with which he could sympathize. Hamilton was arguably the most self-made of our founding fathers: an orphan, born out of wedlock, provincial and all but penniless. His accomplishments as a Revolutionary War soldier and as an American statesman were products of talent and of will. He created our financial system, helped write the Constitution, founded both a political party and The New York Post. He surely would have been president (he surely deserved to be), but fate and an awful little man called Aaron Burr intervened.

Challenged to a duel by Burr, Hamilton thought, wrote, and discussed with his friends why he felt he must accept even though on principle he was opposed to such barbarity. He said his intention would be to “throw his fire,” or aim away from Burr, and let Burr do what he would. In the event Hamilton’s shot went high, striking a tree branch above Burr’s head. We’ll never know whether or not the miss was intentional.

Burr, conversely, aimed true. Hamilton was struck in his lower gut; he suffered catastrophic organ damage and a severed spine. He was instantly paralyzed from the waist down and although he retained consciousness for a while, he knew he was dying.

Alexander Hamilton died the following day, July 12th, 1804.

Hamilton and Burr were both European-Americans, but there’s no tenable reason why Hamilton can’t be convincingly portrayed by the Hispanic Lin-Manuel Miranda, or Burr by the African-American Leslie Odom, Jr. Indeed, there’s a powerful contention that this casting is inspired, and perhaps imperative.

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s ‘Hamilton’ is an embrace of American history by and for a populace that might otherwise disdain our foundational annals. And for all of us it’s a way to rethink and re-celebrate those same stories, in a new and valid and ultimately valuable light.