Cultures clash; they are clashing, as you can plainly see in the news. As long as they’ve bumped up against one another, they’ve clashed.

Cultures clash; they are clashing, as you can plainly see in the news. As long as they’ve bumped up against one another, they’ve clashed.

The differences—the causes of the clashes—are subject to endless debate, and rightfully so. Just as culture itself is a complex, multilayered concept, so too must be the mechanisms by which it causes conflict. So whether you believe that one given culture is reactionary and hypocritical about insults, and doesn’t understand the concept of free speech…or if you believe that another is repressive and condescending, and stirs up furor through calculated humiliation—either way there are equal chances you’re somewhat right, drastically oversimplifying or dangerously misunderstanding of the other side. Such is the nature of cultures trying to understand each other.

It’s complex enough that I can’t and won’t try to plumb those depths here. But another debate, one that doesn’t really offer any insights into or help with solving present events but is still fascinating, is how and why cultures got so combative in the first place. Why has violence, aptitude for and frequent expression of, settled just under the thin skin of civilization?

The usual answers: population pressures, food supply, territoriality, religion. Fair enough. You don’t need to be an historian to see how those have played out.

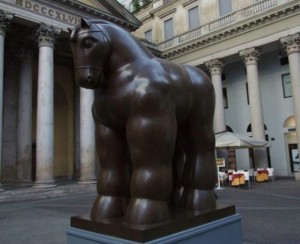

But casting backward a bit further, a bit closer toward the dawn of civilization in its many forms, there’s a somewhat more hidden cultural trigger I’d argue has always tilted societies toward the warlike. That’s the mastery of horse.

But casting backward a bit further, a bit closer toward the dawn of civilization in its many forms, there’s a somewhat more hidden cultural trigger I’d argue has always tilted societies toward the warlike. That’s the mastery of horse.

More peoples than not — at least in population numbers, if not distinct languages, norms, religions, etc. — have domesticated the horse. Horse was hardly the first domesticated animal anywhere; goats, sheep, pigs, and dogs almost always came first. But mastering horse was definitive, and transformative. That mastery brought all the obvious changes: extended range and quicker travel. It enabled more mobile armies and the first battle tactics beyond infantry slog. It brought horsepower to agriculture.

But through all that and more, horse mastery brought much else to culture. It brought metallurgy, or at least the first organized metal-working for purposes other than ceremonial. That new agriculture called for iron plow blades, and the wagons and chariots called for banded wheels. It’s a fact that cultures that grow up with no access to horses, the Australian and American natives primarily, never independently invent the wheel – or at best they never use it for anything but toys. No-horse cultures remain effectively stone-age level, unless and until they make contact with cultures that had mastered the horse.

Does that mean they’re less warlike? Not necessarily. They’re just as subject to the other factors, population pressures and the rest, as any culture. Clearly war, genocide, and all the rest have existed throughout the histories of the people of Australia and North and South America. But without horse, it was always that infantry slog. And it was in the service of countries with human-powered agriculture, that couldn’t afford for their men to be on the march for extended periods. War existed among these cultures, no doubt, but war for them was self-limited. By the lack of horse.

The rest of the world, the great horse-cultures of the Asian, African, and European continents, catapulted out of the stone age and into a still-ongoing march of technology — first grappling with technology related to their horse-driving endeavors, then later for all the things their horsepower enabled. This inevitably includes expansion, subjugation, and slaughter.

horse-driving endeavors, then later for all the things their horsepower enabled. This inevitably includes expansion, subjugation, and slaughter.

Ages later, the descendants of the horse-masters have moved beyond horse, far beyond it. But they’re still channeling that same drive, that conquering spirit, that cultural supremacy that was once spread from horseback.

The problem lies in those pesky numbers. Most civilizations were horse-masters, and all their descendants are elbowing up against each other now. Their ancestors rode in jihads and crusades, cossack charges and Mongol charges. They feel the modern version of that same pull toward the saddle, the drive to ride beyond the horizon carrying the banners of their people. They comprise the majority of the world’s population, at a time when there are few unclaimed horizons and the wrong banner can get you shot.

The hold-outs, the no-horses, have all but disappeared. A few of those cultures, like the Plains Indians, went through an accelerated version of horse mastery, after meeting up with horseback invaders, and did indeed make the horse the center of their lives. It happened in the space of a couple hundred years, instead of thousands. But that was still just a deviation, for the ultimate fate of the stone-age cultures in a horse-influenced world, is to be absorbed and to all but disappear.

Yet every now and then you hear of those uncontacted tribes, usually way up the Amazon somewhere, that are still hunting with bows and arrows and had not a notion of white people or airplanes or a world beyond the rain forest. Or of horses.

They don’t stand a chance. The world’s too small now for anyone to remain uncontacted, unabsorbed. At best they can hold out a while, or do-gooders can try to protect them for a while…but their fate as a people is sealed.

This all rings true, I think, but it doesn’t help much, does it? Knowing the earliest reasons your culture got out its knives doesn’t much point the way to putting them away. At best I’ve offered you a little cultural introspection.

But maybe you can get something from that. Maybe it can help you delve the reasons why you and your people thump your chests and throw your elbows. You and your people, and the horse you rode in on.