With this week’s announcement of the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature, the world’s cultural attention has turned to Chinese literature. China has one of the world’s most ancient traditions of written art, yet has been mostly ignored by the Nobel committee until now. The award of the 2012 literature prize to author Mo Yan has begun to rectify that.

With this week’s announcement of the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature, the world’s cultural attention has turned to Chinese literature. China has one of the world’s most ancient traditions of written art, yet has been mostly ignored by the Nobel committee until now. The award of the 2012 literature prize to author Mo Yan has begun to rectify that.

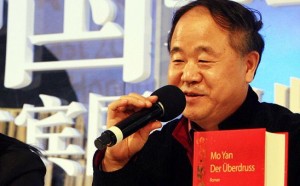

Mo Yan, author of Red Sorghum and The Republic of Wine, was saluted by Nobel’s Swedish Academy for his “hallucinatory realism,” which has been compared to the style of Franz Kafka. The Kafka-esque comparison is enhanced by an examination of Mo Yan’s life, and even his presumably allegorical pen name (Mo Yan translates to “Don’t Speak”).

Guan Moye (the author’s real name) has been criticized for his closeness to China’s ruling communist party, yet his work has been among the most censored in China. He was born to a farming family in Shandong Province, had some early schooling, but was forced to quit at a young age and turned to hard labor during the Cultural Revolution. He later joined the People’s Liberation Army, and it was while he was still a soldier, in the early ’80s, that he began his writing career.

Chinese émigrés have won the Literature prize before (including Gao Xingjian in 2000), and even the 1938 winner, Pearl Buck, might be seen as a representative of the Chinese cultural tradition on the world stage. But as the first Chinese national to win what many consider to be the pinnacle of recognition for writers, Mo Yan has brought a new global focus to China’s modern ascendancy. His own talent and body of work, one hopes, is the true incitation for this award; still, it’s hard not to think that this award is more proof that in cultural matters (in addition to countless others), our present times might well be remembered as the Chinese century.