I try not to too often use this soapbox as a dispensary for artistic advice (my good friend Robin K. has that all sewn up for writers over at More Ink and for visual artists at Ink and Alchemy).

I try not to too often use this soapbox as a dispensary for artistic advice (my good friend Robin K. has that all sewn up for writers over at More Ink and for visual artists at Ink and Alchemy).

But I’m nothing but willing to break my own rules, particularly when stimulated to do so. At the moment I’m under the sway of two unrelated bits of stimuli: just read a fascinating yet chuckle-worthy article at Cracked.com called 5 Famous Writers With Flaws Everyone Tries To Ignore. It’s an eye-opener.

Second is a book I’m currently reading—Killing the Buddha: A Heretic’s Bible. That title, and the  mindset it’s given me, deserves a bit of explanation. It comes from an old Buddhist adage that goes something like this: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, you must kill him.” Which sounds strangely deicidal, and is doubly strange since Buddhism is essentially a religion without godhead.

mindset it’s given me, deserves a bit of explanation. It comes from an old Buddhist adage that goes something like this: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, you must kill him.” Which sounds strangely deicidal, and is doubly strange since Buddhism is essentially a religion without godhead.

No, what the sages are telling you is that hero-worship stands firmly in the way of enlightenment. It means that you might admire Buddha (or whomever) but too much uncritical admiration is self-destructive. The only defense against that is hero-murder. So if you meet your hero on the road, you must kill him (preferably symbolically).

The Cracked article, for its part, did some good hero-deflating of icons like Dickens, Orwell, even good old Willy Shakes.

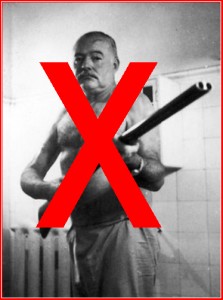

But they missed one of my personal Buddhas. So for the sake of my own enlightenment, or at least for my growth as a writer, I’m going to enumerate a couple of the flaws that have always irked me about the writing of Ernest Hemingway.

I’ve written here about Hemingway once or twice, but for some reason (see “hero worship,” above) I’ve never pointed out what I now realize are real problems with his body of work….

So let’s talk about characterization. Ernest Hemingway was more than capable of crafting truly complex, layered, and very human characters…but only as long as they were white men who reminded him of himself. So a Hemingway character who happened to be a two-fisted unflinching manly man, accustomed to handling adversity without so much as a whimper, was written with the aplomb one might expect from a Pulitzer and Nobel Prize winner. By way of example I’d offer up Nick Adams, Jake Barnes, Harry Morgan, Frederic Henry, Robert Jordan, and others too numerous to mention.

But women? Hemingway famously didn’t have much respect for women; read any of his biographies and you’ll quickly come to suspect he had some thorny mommy issues. In his writing, with some notable exceptions, women are thinly constructed, weak-willed caricatures. They swoon, they’re indecisive, they’re lost without those strong men. For each of the male examples cited above, from his major novels like For Whom The Bell Tolls, The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell To Arms, and To Have And Have Not, the female lead characters are (this kills me to say) badly written.

And most egregiously, in my eyes, is Hemingway’s treatment of race. Actually, if I’m to kill this Buddha, I have to amend that: Hemingway was, far too often, gratuitously racist.

Was he a product of his times? Maybe, but it’s too easy to let him off the hook that way. He was famous in his time. By the age of forty he was pretty much understood to be one of the greatest living writers of fiction. He must have known that his writing would be studied and appreciated far beyond his lifetime. And he should have understood—if any part of your writing has to be someday explained away with, “Well, that’s just how people thought then,” then you have to change it.

I’m not going to go into a lot of detail here, because that’d force me to quote some lines that include ugly, despicable words and phrases that I’d just as soon let die. Suffice it to say that when Hemingway introduced a non-caucasian character (and that, shamefully, wasn’t often) he did so with slurs and stereotypes that served no lyrical purpose. They only seemed to serve his own prejudices. For me, that damned near ruins otherwise near-flawless books, including The Sun Also Rises and To Have And Have Not.

Let’s be clear. Hemingway deserved that Pulitzer. He probably deserved the Nobel (although that’s arguable, since its impetus was The Old Man And The Sea—not his best work). Hemingway was, is, and always shall be one of literature’s true masters of prose. Hell, his poetry ain’t bad either.

But he’s not quite the unassailable Buddha that I, and probably others, have set him up to be. So follow my lead: If you ever meet Ernest Hemingway on the road, sure, go ahead and tell him you admire him. Buy him a drink; he’d like that. Get him drunk and arm-wrestle him. He’d love it.

But then tell him this, and mean it: “You can’t mess with my head anymore, Ernie. I’ve already killed you.”