Crises have a way of bringing out the best or the worst in people, and in societies, and in cultures. There’s rarely a middle ground, and there’s rarely any ambiguity to it. You might think of them as litmus tests for collective character.

Crises have a way of bringing out the best or the worst in people, and in societies, and in cultures. There’s rarely a middle ground, and there’s rarely any ambiguity to it. You might think of them as litmus tests for collective character.

Economic crises, as recent experience has shown, tend to rub rawest. They strike average people the hardest, and leave those people all but powerless while destroying their ability to cope with the present or to strive for the future. Being products of amorphous “market forces” they rarely create a rallying figure, an enemy to fight, a cause to muster for or against. Their effects, usually, are internalized. We’re all left to fight, or more often to founder, alone.

But it hasn’t always been like that.

The worst economic crisis in modern history began, arguably, in 1929—it spread around the world and lasted for more than a decade. Its precise causes are debatable but it is generally agreed that it started with the collapse of American markets (the Black Tuesday stock market crash in October 1929 was a symptom, not a cause), as well as the failure American banks, and was fatally exacerbated by rampant unemployment. At the midway point of what was by then being called the Great Depression, 15 million Americans—representing almost a quarter of the working class—were unemployed, and nearly half of American banks had closed their doors forever.

Politics, as ever, was handmaiden to economics; and political gutter-fighting, then as now, impeded economic policy. A major difference, beginning in 1932, was leadership. The election of Franklin Roosevelt brought fresh perspectives and new ideas. His radical solutions were by no means universally embraced, but they (and more importantly, he) were popular enough to clear the way for unprecedented experimentation: economic stimulus backed by the full force of the federal treasury.

policy. A major difference, beginning in 1932, was leadership. The election of Franklin Roosevelt brought fresh perspectives and new ideas. His radical solutions were by no means universally embraced, but they (and more importantly, he) were popular enough to clear the way for unprecedented experimentation: economic stimulus backed by the full force of the federal treasury.

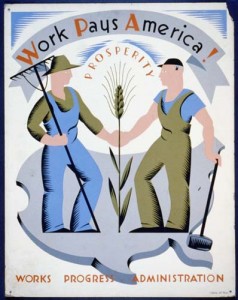

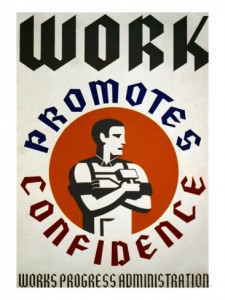

Under the general banner of The New Deal, managed by an array of novel Alphabet Soup agencies, and exemplified by the WPA (Works Progress Administration), America rolled up its sleeves and got back to work.

Recent experience, again, has shown that controversial is the kindest possible term for the idea that federal dollars (and more importantly, federal oversight) can lead to economic recovery. And it would be controversial, or at least impossible to prove, to say that the New Deal overcame the Great Depression.

But what is beyond debate is this: it put people back to work.

If you know where to look, you can still find the legacy of the New Deal in every state, in nearly every city and town. Schools, libraries, roads, bridges—massive infrastructure projects and tiny improvements on the landscape. It was all created by collective effort, in a collective struggle to rebuild a wounded country.

town. Schools, libraries, roads, bridges—massive infrastructure projects and tiny improvements on the landscape. It was all created by collective effort, in a collective struggle to rebuild a wounded country.

As evidence of the farsightedness of these programs (you might call it progressive, which had not yet become a dirty word), they recognized that it wasn’t just the laborer who was suffering, and it wasn’t only the laborer who could contribute.

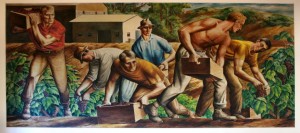

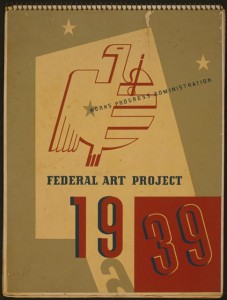

The Federal Arts Project, an extension of the WPA, began in 1935 to employ out-of-work painters, sculptors, and art teachers in public works projects and programs. The idea is almost unthinkable now, but it recognized two truths: that art is funded by surplus (and thus, it withers during lean times), and that it is culturally worthy of support.

Nearly a quarter of a million works of art—murals, posters, public sculptures—were created. Among the most iconic were the inspirational murals, often gracing the walls of new WPA-constructed post offices. The style was realist, modern, unceasingly optimistic. Created of necessity—it was essentially the mode of anti-Depression propaganda—it became a fashion unto itself, one that’s still mightily influential today.

Nearly a quarter of a million works of art—murals, posters, public sculptures—were created. Among the most iconic were the inspirational murals, often gracing the walls of new WPA-constructed post offices. The style was realist, modern, unceasingly optimistic. Created of necessity—it was essentially the mode of anti-Depression propaganda—it became a fashion unto itself, one that’s still mightily influential today.

Sadly, preservation of these works has never been a national priority. Their neglect almost gives credence to the argument that they were nothing but busy-work for the Jackson Pollocks and Mark Rothkos employed by the WPA; an embarrassing artists’ welfare program, best forgotten. The vast majority of the original artwork is simply gone.

national priority. Their neglect almost gives credence to the argument that they were nothing but busy-work for the Jackson Pollocks and Mark Rothkos employed by the WPA; an embarrassing artists’ welfare program, best forgotten. The vast majority of the original artwork is simply gone.

So be it. Public art and public-art funding are, as demonstrated, controversial, and it’d be a long-shot on a good day to get all Americans, or even a respectable plurality, to grow sentimental over what can be reasonably termed ‘artistic socialism.’ Such a movement can probably never happen here again.

But I’m writing these words on an American public holiday, one that for some smells of socialism, and for others represents a grudging nod to the value of the U.S. working class. I can think of no better day than Labor Day to remember that once upon a time, art was labor.

We’ll never see public arts sponsorship on this scale again, and there’s a sad but distinct chance we won’t see its production, its original output, for very much longer. I can’t say if that’s the result of neglect or purposeful design, but either way this legacy is being erased.

We’ll never see public arts sponsorship on this scale again, and there’s a sad but distinct chance we won’t see its production, its original output, for very much longer. I can’t say if that’s the result of neglect or purposeful design, but either way this legacy is being erased.

*

Best we can do, I suppose, is remember it. And maybe while we’re doing so we can ponder what that program said about America then, and what its disregard says about us now.