Libraries are living institutions, and that’s as unerringly true whether they’re public lenders or personal collections. In either case they’re bound to grow, as long as people care enough to nurture them.

Libraries are living institutions, and that’s as unerringly true whether they’re public lenders or personal collections. In either case they’re bound to grow, as long as people care enough to nurture them.

But they retract, too. Or shed, you might say. Volumes become redundant or go unread, they gather dust for a bit until space is needed. And then they have to go.

In a just world, they’d never be destroyed, but this world of ours has never been just. Books are burned everywhere, every day (and yes, your public library does it too), and somehow it stings more to hear of it happening for these most mundane, most utilitarian reasons. But fortunately, that’s not always the ex libris fate.

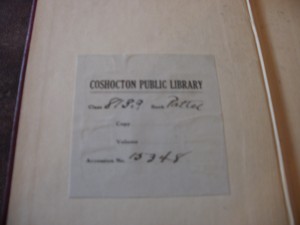

Ex Libris: from the library. Think of it as the taxonomic name for a second-hand book. If you buy used books ( firstly, thank you), you surely have some awareness of their history, the meandering path they took to arrive on your shelf. They might have originated as public-library volumes or as personal property; you checked the inside covers, probably before you even purchased them, and you saw. You touched upon that history.

firstly, thank you), you surely have some awareness of their history, the meandering path they took to arrive on your shelf. They might have originated as public-library volumes or as personal property; you checked the inside covers, probably before you even purchased them, and you saw. You touched upon that history.

◘

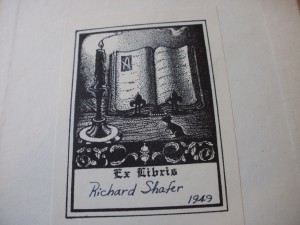

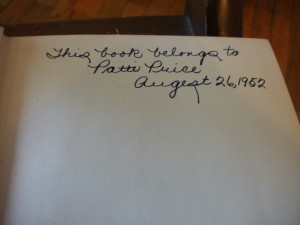

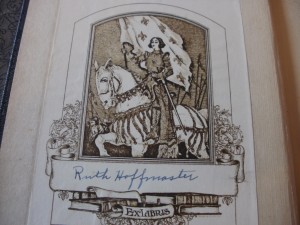

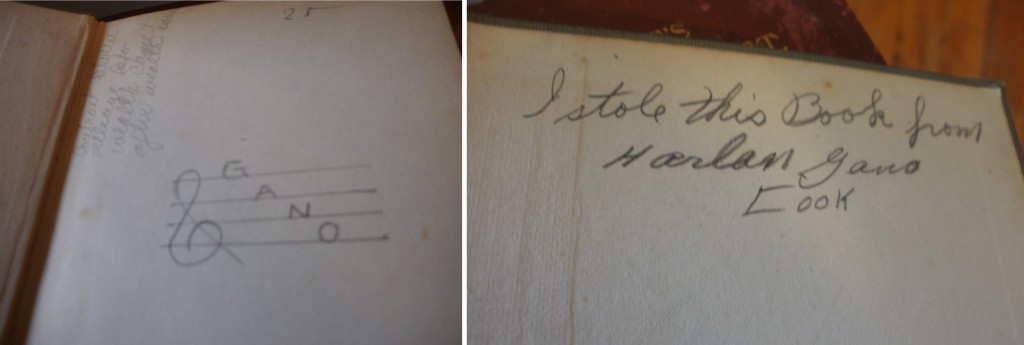

The personal brandings you find are nothing less than enchanting. I’ve talked before at length on marginalia, but this isn’t quite the same thing. I’m speaking here of the way people mark their books as their own—from simply inking their names in, to much more elaborate rites. It must have been for their own edification, mostly, and to remind trusted friends of to whom borrowed books must be returned. Whatever the long-lost motive, I’m forever finding handwritten and glued-in colophons that in themselves contribute to our precious body of  literature and art…

literature and art…

◘

◘

◘

◘

◘

◘

◘

◘

◘◘

You can learn a bit, unexpectedly, about people so far removed that you can be sure you’ll never meet them. Not always just their names, but also sometimes something of their character—that’s how I met Harlan Gano, in my own way, and found that not only did he have an unconventional way of signing his name, he was also rather impish in shaming would be thieves:

◘

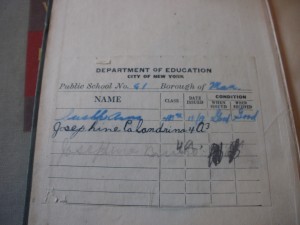

And there’s wider and deeper history to be had, like in a schoolbook from the twenties from P.S. 61 in Manhattan. Was ‘Josephine’ an especially popular name there and then? Was the neighborhood predominately Italian? All I have are these sparse and captivating clues…

Manhattan. Was ‘Josephine’ an especially popular name there and then? Was the neighborhood predominately Italian? All I have are these sparse and captivating clues…

◘

◘

◘

◘

◘

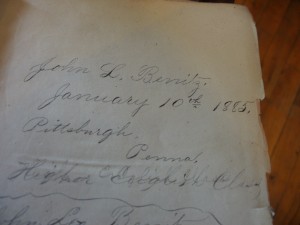

But then, sometimes more exact evidence is presented, and more distant history is accessible. I can’t say for certain that it’ll ever benefit me to know that John L. Benitz was studying rhetoric in his higher English class in Pittsburgh on the 10th of January, 1885…but I like knowing it regardless.

◘

◘

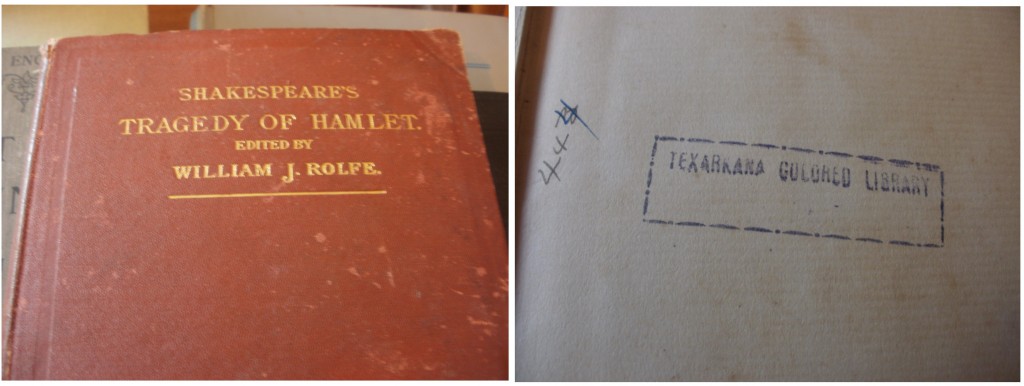

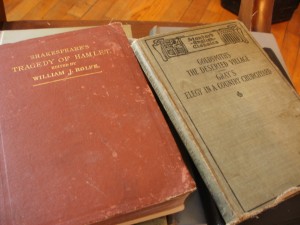

Not all history is equally alluring, though. Take as evidence this volume of Hamlet—soaring literature that belongs to us all, as a cultural birthright. Yet at one time even books, even the best books, supplemented disharmony and inequality:

All of that, the gripping and the regrettable—that’s why I’m a collector. Books don’t just tell stories, they are stories. The books I collect found their way from someone else’s library to mine, and brought with them their own tales. It doesn’t matter much if I can decode those narratives, in whole or even in part. It just matters that they’re there.

are stories. The books I collect found their way from someone else’s library to mine, and brought with them their own tales. It doesn’t matter much if I can decode those narratives, in whole or even in part. It just matters that they’re there.

◘

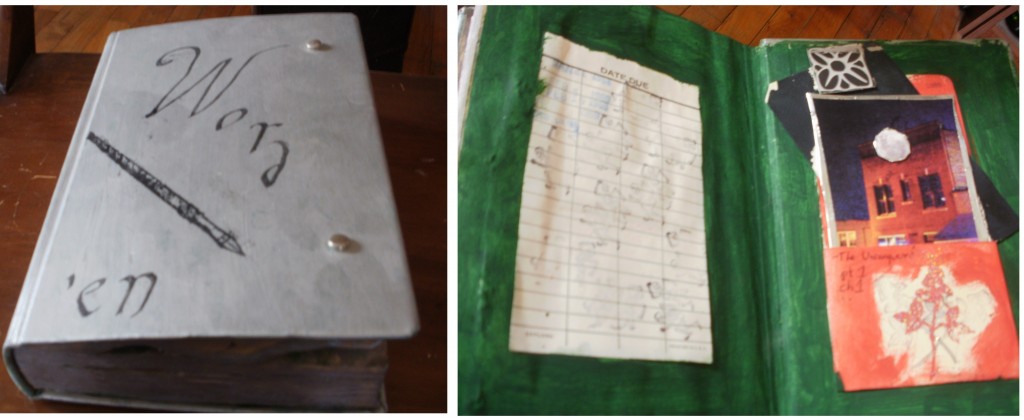

As for branding my own books, inking in my own name or some little part of my own story, I rarely do that. I’m not really sure why. Maybe I just think that my personal history is insignificant compared to the longer, more varied journeys the books will travel, should the stars align and they be permitted to do so. Only on the rarest occasion have I marred books (never feeling right about it); I’ve made a few art books, for instance. But in doing so I’ve always been compelled to somehow honor their histories. This one, for example, had years earlier been discarded by the Akron Public Library. The vestiges of that needed to be integrated into the final product:

I have to allow, though, that Ex libris and This book belongs to and even I stole this book from weren’t put there for my enjoyment, but were rather affirmations of value. As someone who counts his wealth in books, I get that. Marking a book as one’s own might perhaps preserve and protect its ownership for a while, but sooner or later it’s going to end up where it’s going to end up. I might value my books, but much more than that, I respect their fate.

If I truly needed to safeguard a book from sticky fingers, however, I might instead of writing my name it, try out the effectiveness of a certain incantation I’ve recently learned was used to protect medieval books from “him that stealeth, or borroweth and returneth not, this book from its owner“…

Let him be struck with palsy, and all his members blasted. Let him languish in pain crying aloud for mercy, and let there be no surcease to his agony till he sing in dissolution. Let bookworms gnaw his entrails…and when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of hell consume him forever.