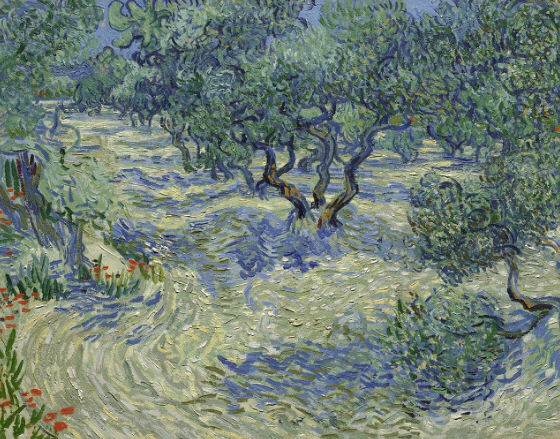

Call it a hazard of painting plein air (or maybe call it, “stilled life”). Vincent Van Gogh, mostly known for his sweetly tragic tenure, is nearly as celebrated for his extraordinary oil-painting technique and masterful interpretation of nature. Like the majority of his landscapes, Olive Trees (1889) was created outdoors, in the elements, amidst the artist’s inspiration. That setting, along with Van Gogh’s habit of deeply layering whorls of paint, has produced a 128-year-old surprise.

Call it a hazard of painting plein air (or maybe call it, “stilled life”). Vincent Van Gogh, mostly known for his sweetly tragic tenure, is nearly as celebrated for his extraordinary oil-painting technique and masterful interpretation of nature. Like the majority of his landscapes, Olive Trees (1889) was created outdoors, in the elements, amidst the artist’s inspiration. That setting, along with Van Gogh’s habit of deeply layering whorls of paint, has produced a 128-year-old surprise.

During recent study to update the artwork’s catalog entry, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which has owned Olive Trees since 1932, discovered the remains of a small, very dead grasshopper locked within the oil paint in the lower foreground. The carcass is essentially microscopic, and is not visible to the naked eye.

During recent study to update the artwork’s catalog entry, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which has owned Olive Trees since 1932, discovered the remains of a small, very dead grasshopper locked within the oil paint in the lower foreground. The carcass is essentially microscopic, and is not visible to the naked eye.

Curators contacted investigative entomologists, in hopes that examination of the insect might offer insight into Van Gogh’s process, and perhaps might identify the season in which Olive Trees was painted.

Unfortunately little could be discerned—the thorax and abdomen of the grasshopper are missing, complicating species identification. The experts did note that the surrounding paint did not seem to be disturbed, suggesting that the grasshopper was already dead when it landed on the canvas. Most likely it was wind-borne.

Interestingly, this was a phenomenon that Van Gogh seemed to be familiar with. In a letter to his brother, penned a few years before the creation of Olive Trees, he wrote, “…I must have picked up a good hundred flies and more off the four canvases you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand…”.

So is there a lesson to be learned from this well-traveled bug’s misadventure, or is it merely an art-history curiosity? Hard to say. Maybe it simply presents an apt metaphor: Do you yearn to learn more about Van Gogh, about painting, about art, about life? Then all you need to do is take a closer look.