Opportunities to learn pop up quite unexpectedly. You have to be ready to seize them, to revel in them, and yes, to begin learning from them. Their unpredictability demands that.

Take for instance my new-found fascination with the life of Sir Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St. Alban, 1st Baron Verulam. Not long ago I knew that there had been a Francis Bacon, that he was mostly remembered as a philosopher, and that he was sometimes theorized to be the true author of the works of Shakespeare. And that was about all I knew. Then I went to a flea market.

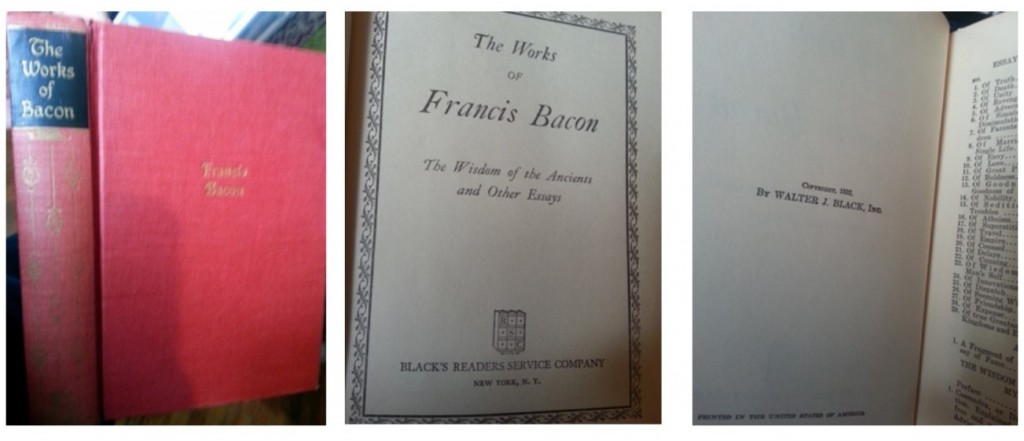

Here it is, my four-dollar-flea-market-find. A remarkable book, now a treasured part of my collection (never mind that it really did only cost $4). It’s what prompted me to learn a bit more about Master Francis Bacon:

I’m working my way through these writings, which have titles like Of Truth, Of Death, Of Followers and Friends, and The Wisdom of the Ancients. They speak of a staggering body of knowledge from this exemplar of the English Renaissance, who is only approximately and somewhat inaccurately described as a philosopher. Philosophy was one of his interests, no doubt, but so was just about everything else. He’s probably better summarized as a polymath. And his writings, being very personal documents written in the first person, through which he bolsters daring arguments and shares arcane scholarship, lead me to suggest in all humility that if he were alive today he’d be a blogger.

I’m working my way through these writings, which have titles like Of Truth, Of Death, Of Followers and Friends, and The Wisdom of the Ancients. They speak of a staggering body of knowledge from this exemplar of the English Renaissance, who is only approximately and somewhat inaccurately described as a philosopher. Philosophy was one of his interests, no doubt, but so was just about everything else. He’s probably better summarized as a polymath. And his writings, being very personal documents written in the first person, through which he bolsters daring arguments and shares arcane scholarship, lead me to suggest in all humility that if he were alive today he’d be a blogger.

Francis Bacon was born in London in 1561 to a family that was well-connected, yet hardly aristocratic and far from rich. His entire life seemed to be a struggle to transcend what he perceived to be the lowliness of his family’s circumstances. And  though he did that, eventually becoming a counselor to successive monarchs and a nobleman himself, his social climbing came at great cost. Indeed, there seems to have been two very different Francis Bacons: the erudite man of learning and letters, and the political creature who wasn’t above betrayal and corruption. His is a very complex, very human story.

though he did that, eventually becoming a counselor to successive monarchs and a nobleman himself, his social climbing came at great cost. Indeed, there seems to have been two very different Francis Bacons: the erudite man of learning and letters, and the political creature who wasn’t above betrayal and corruption. His is a very complex, very human story.

His intelligence was legendary. Indeed, he seems to have been a child prodigy, starting his education at Trinity College at age 12, being called to the bar while still a teenager, and becoming a member of Parliament at 20.

Through the course of his life he’d become Attorney General under Queen Elizabeth I, Lord Chancellor to King James I, and created by the latter both Viscount and Baron not long before his death. It’s interesting to note that both peerages were created for Bacon, and both became extinct upon his death, as he died without heirs.

Being ennobled was the culmination of his very ambitious, not entirely honorable political career—a career that saw him publicly betray, when it became expedient to do so, his former patron, the 2nd Earl of Essex. He also curried favor with Elizabeth as she consolidated her power by openly agitating for the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. Having finally been granted land, titles, and responsibility, he was to see it all slip through his fingers.  Within a few years he was arrested for indebtedness, accused by Parliament of dozens of separate acts of corruption, briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London, and finally barred from holding public office. Five years later he was dead.

Within a few years he was arrested for indebtedness, accused by Parliament of dozens of separate acts of corruption, briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London, and finally barred from holding public office. Five years later he was dead.

Now how can we reconcile that unseemly biography with that of the scientist, philosopher, and writer? His political career tarnished his character and reputation, to the point where his contemporaries might have wondered if he could ever be rehabilitated.

But he can and should be, because there’s a good chance that many of us alive today, maybe even most of us, owe our very lives to Francis Bacon. Bacon was the father of the scientific method—the practice of investigation through empirical observation. It’s the root of almost all scientific discovery in the modern era, so familiar that most of us don’t stop to wonder where it came from. But its alternate appellation, “the Baconian method,” gives us an inkling as to how important this man was to the evolution of learning. He died for it in fact, contracting pneumonia while experimenting with the use of freezing temperatures for the preservation of food.

His is, as I’ve said, a complex and fascinating story. I’ve only just begun to scratch its surface. Like Bacon, I’d like to dedicate myself to learning more, continuously, because this is a subject I could spend a lifetime on and still not come close to exhausting.

I knew that was true when I flipped to the last page of my remarkable flea-market treasure, and saw the final lines he penned for his Wisdom of the Ancients essay. It was a glimpse, I think, into his deepest motivations, and I’d like to think it’s an excuse for his worst failings and excesses:

“For contemplations exceed the pleasures of sense, not only in power but also in sweetness.”