There’s a little mental calculus that comes into play when you’re thinking about attending a political event. First off there are the known disincentives: There’ll be long lines and lots of waiting. Decibel levels will be high. Spirits will also be high, and that can be a good or bad thing. Then there are the things that could happen–the entire spectrum of crazy that’s liable to come out and play. At best it’s a crapshoot.

There’s a little mental calculus that comes into play when you’re thinking about attending a political event. First off there are the known disincentives: There’ll be long lines and lots of waiting. Decibel levels will be high. Spirits will also be high, and that can be a good or bad thing. Then there are the things that could happen–the entire spectrum of crazy that’s liable to come out and play. At best it’s a crapshoot.

Outweighing all that, for me at least, was the fact that on Monday, October 3rd, Hillary Clinton spoke not just in my city, not just in my neighborhood, but literally down the road from my house. Odds of craziness notwithstanding, how could I not go?

The entire experience cost me about 3 hours, give or take, from the time I walked out my front door until I walked back in. Most of that time was indeed spent standing, queuing, waiting. A few hundred of us (rough estimate) stood in two long lines stretching out from the main doors of the venue, down the street and around the corner. There were a handful of protesters of the “Hillary for Prison” variety; I heard a few rancorous exchanges but for the most part the folks standing in line refrained from engaging. There was one gentleman, picketing back and forth on the other side of the street, holding forth with great gusto on (I assume) all he hated and feared about HRC. There were two lanes of rush-hour traffic separating us, though. I overheard someone else in the line say, “That guy is about to give himself a stroke, and I can’t hear a word he’s saying. Win-win.”

walked back in. Most of that time was indeed spent standing, queuing, waiting. A few hundred of us (rough estimate) stood in two long lines stretching out from the main doors of the venue, down the street and around the corner. There were a handful of protesters of the “Hillary for Prison” variety; I heard a few rancorous exchanges but for the most part the folks standing in line refrained from engaging. There was one gentleman, picketing back and forth on the other side of the street, holding forth with great gusto on (I assume) all he hated and feared about HRC. There were two lanes of rush-hour traffic separating us, though. I overheard someone else in the line say, “That guy is about to give himself a stroke, and I can’t hear a word he’s saying. Win-win.”

Eventually we filed in, and made our way to stadium seating an an upper tier, or for yet more standing on the  event-hall floor. I chose the latter and ended up not more than 20 feet from the podium. More waiting ensued, predictably, then finally the warm-up speakers: local party people, then the mayor, a couple members of Congress, then finally the speaker herself.

event-hall floor. I chose the latter and ended up not more than 20 feet from the podium. More waiting ensued, predictably, then finally the warm-up speakers: local party people, then the mayor, a couple members of Congress, then finally the speaker herself.

If you’ve followed even a modest amount of politics, you probably have a decent idea of how events like this unfold. I saw and heard nothing particularly unexpected in that respect. I’d heard that Clinton’s speech would be one on economic policy, and although that and a lot of other ground (national security, education, not much alas on the environment) was covered, she spent at least half her time attacking her opponent. That’s a predictable political reality, I suppose, but I found it nevertheless disappointing. And on a pragmatic level, I wonder if it was even necessary—Trump seems to be doing fine crashing his own campaign with his own words and deeds. Me and Ali prescribe a rope-a-dope strategy.

opponent. That’s a predictable political reality, I suppose, but I found it nevertheless disappointing. And on a pragmatic level, I wonder if it was even necessary—Trump seems to be doing fine crashing his own campaign with his own words and deeds. Me and Ali prescribe a rope-a-dope strategy.

But in any case, it wasn’t a bad speech. The delivery was better than I expected—she spoke with notes, no Teleprompter, and she was much more engaged (and engaging) than I’ve seen in all too many of her appearances. She also looked pretty damned good for someone weathering a bout of pneumonia just three weeks ago.

All that time, though, I was less interested in the speaker in front of me than in the people all around me. The turnout, in size and demography, was surprising and encouraging. The crowd looked like my city. All ages, all races; a larger number than I would have expected, frankly, of guys a lot like me: white and over forty. Even better, all of these people were just plain nice. In tight quarters, where toes were inevitably stepped on and all the unavoidable jostling occurred, I heard not a single angry word. All around me, people were simply being  kind to each other, striking up conversations and, I’m sure, striking up more than a few new friendships.

kind to each other, striking up conversations and, I’m sure, striking up more than a few new friendships.

Above all else, though, what I found most encouraging as I looked around, was the number of millennials in attendance. This much-maligned generation—probably the most unfairly heaped-upon generation in history—was out in force, and that prompted me to reevaluate them in depth. The many accusations against these young people includes the one about being politically (even civilly) disconnected. Twenty-somethings and thirty-somethings made up not just a plurality of the crowd, as far as I could see, but also a majority of the campaign staff. So if there’s a disconnection somewhere, it isn’t with them.

Millennials are also accused of being self-centered, of being coddled, of coming up with the sense of entitlement that comes with being in that ‘everyone gets an award’ generation. Well, I wasn’t likely to confirm or deny any of that based on a three-hour political rally, but then again I didn’t see any need to try. Because even a moment’s worth of thinking on it reveals how ball-bustingly unfair those accusations are. Millennial attitudes and mind-sets, for good or ill, are the products of the people who raised them. Millennials didn’t invent the concept of passing out awards for showing up—the previous generation did, and the millennials just happened to be the guinea pigs on whom the idea was tried out.

They’ve grown up in a world where they’ve been able to take for granted the ubiquity of advanced technology, yet they’ve been showered with constant blaring assertions that this, right now, is the worst things have ever been. When they were small we told them they must go to college if they ever hoped to make something of their life, then we handed them an economy and a job market where their degrees were more like extremely expensive jokes.

They’ve also come of age at a time when perpetual war and looming environmental crises come with the territory. The costs of both of these are to be paid, disproportionately, by the millennial generation and the generations that come after.

I realized, then, with the unlikely backdrop and impetus of a Hillary Clinton rally, that against all odds and contrary to the lousy hand they’ve been dealt, the millennial generation are doing their best to, well, make America great again.

When I left I was hardly thinking about Hillary Clinton or this chancre-sore of an election. I left feeling very, very optimistic.

.This is the time of year that most of us are trying to keep the elements out. Safe and warm cocoons are just a single door-seal removed from the bluster and bullshit raging out there, and all around.

.This is the time of year that most of us are trying to keep the elements out. Safe and warm cocoons are just a single door-seal removed from the bluster and bullshit raging out there, and all around.

It’s unfathomable.

It’s unfathomable.

should note for the sake of accuracy that only 1 percent of that 2.7 is actually clean and within reach and the ultimate irony if not patent proof of our unfitness for being is that even that freshest and most accessible water would still kill us no shit in 4 minutes or less in if we just shove our face in it.

should note for the sake of accuracy that only 1 percent of that 2.7 is actually clean and within reach and the ultimate irony if not patent proof of our unfitness for being is that even that freshest and most accessible water would still kill us no shit in 4 minutes or less in if we just shove our face in it.

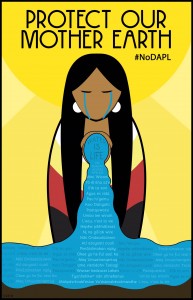

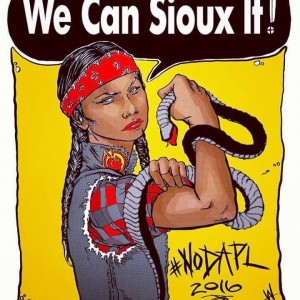

Months have passed and seasons have changed, and the

Months have passed and seasons have changed, and the  Defenders

Defenders dignity, as completely and assuredly as it ever did in our dark and shameful centuries past.

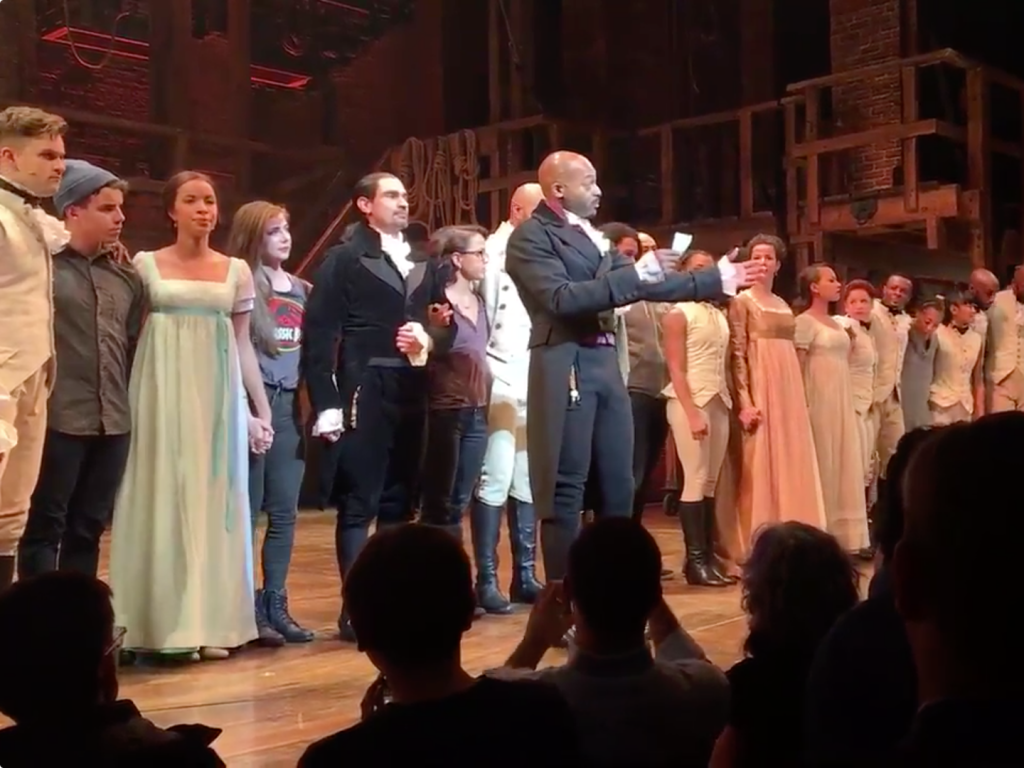

dignity, as completely and assuredly as it ever did in our dark and shameful centuries past. Culture and current events intersected, as they do, when this weekend Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended the Broadway mega-hit musical,

Culture and current events intersected, as they do, when this weekend Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended the Broadway mega-hit musical,  cheers) upon his entrance, and with with a stirring appeal from the cast at the play’s end.

cheers) upon his entrance, and with with a stirring appeal from the cast at the play’s end. From our lips he drew the

From our lips he drew the  Politics is nasty, bloody sport. Maybe we say this every go-round, maybe I’ve said it too often myself—but this time it’s nastier, bloodier, so much more repulsive than we’ve seen…than we deserve…than we’re capable of.

Politics is nasty, bloody sport. Maybe we say this every go-round, maybe I’ve said it too often myself—but this time it’s nastier, bloodier, so much more repulsive than we’ve seen…than we deserve…than we’re capable of.

So what we have here is a coast-to-coast metaphor, spotted

So what we have here is a coast-to-coast metaphor, spotted  There’s a little mental calculus that comes into play when you’re thinking about attending a political event. First off there are the known disincentives: There’ll be long lines and lots of waiting. Decibel levels will be high. Spirits will also be high, and that can be a good or bad thing. Then there are the things that could happen–the entire spectrum of crazy that’s liable to come out and play. At best it’s a crapshoot.

There’s a little mental calculus that comes into play when you’re thinking about attending a political event. First off there are the known disincentives: There’ll be long lines and lots of waiting. Decibel levels will be high. Spirits will also be high, and that can be a good or bad thing. Then there are the things that could happen–the entire spectrum of crazy that’s liable to come out and play. At best it’s a crapshoot. walked back in. Most of that time was indeed spent standing, queuing, waiting. A few hundred of us (rough estimate) stood in two long lines stretching out from the main doors of the venue, down the street and around the corner. There were a handful of protesters of the “Hillary for Prison” variety; I heard a few rancorous exchanges but for the most part the folks standing in line refrained from engaging. There was one gentleman, picketing back and forth on the other side of the street, holding forth with great gusto on (I assume) all he hated and feared about HRC. There were two lanes of rush-hour traffic separating us, though. I overheard someone else in the line say, “That guy is about to give himself a stroke, and I can’t hear a word he’s saying. Win-win.”

walked back in. Most of that time was indeed spent standing, queuing, waiting. A few hundred of us (rough estimate) stood in two long lines stretching out from the main doors of the venue, down the street and around the corner. There were a handful of protesters of the “Hillary for Prison” variety; I heard a few rancorous exchanges but for the most part the folks standing in line refrained from engaging. There was one gentleman, picketing back and forth on the other side of the street, holding forth with great gusto on (I assume) all he hated and feared about HRC. There were two lanes of rush-hour traffic separating us, though. I overheard someone else in the line say, “That guy is about to give himself a stroke, and I can’t hear a word he’s saying. Win-win.” event-hall floor. I chose the latter and ended up not more than 20 feet from the podium. More waiting ensued, predictably, then finally the warm-up speakers: local party people, then the mayor, a couple members of Congress, then finally the speaker herself.

event-hall floor. I chose the latter and ended up not more than 20 feet from the podium. More waiting ensued, predictably, then finally the warm-up speakers: local party people, then the mayor, a couple members of Congress, then finally the speaker herself. opponent. That’s a predictable political reality, I suppose, but I found it nevertheless disappointing. And on a pragmatic level, I wonder if it was even necessary—Trump seems to be doing fine crashing his own campaign with his own words and deeds. Me and Ali prescribe a rope-a-dope strategy.

opponent. That’s a predictable political reality, I suppose, but I found it nevertheless disappointing. And on a pragmatic level, I wonder if it was even necessary—Trump seems to be doing fine crashing his own campaign with his own words and deeds. Me and Ali prescribe a rope-a-dope strategy. kind to each other, striking up conversations and, I’m sure, striking up more than a few new friendships.

kind to each other, striking up conversations and, I’m sure, striking up more than a few new friendships. Today is Leonard Cohen’s 82nd birthday. He isn’t resting easy, though, no matter how well that rest might be deserved. After 49 years (and counting) in the music business, and 13 studio albums to his credit, this anti-crooner and songwriting tour de force is still hard at it. His 14th album, You Want it Darker drops one month from today. He’s been kind enough, though, to share his birthday tidings with us all by releasing the title track, embedded below. It is gravelly gravitas, just like his entire body of work. To honor that retrospective, I’ve also included a wee slice of his older work, including that one gorgeous hymn that’s so often imitated, and so far from duplicated (“I hate that song,” the missus said once as we listened to some anonymous hack mangle it. “Oh but darlin’, you haven’t heard Leonard sing it.”). Enjoy.

Today is Leonard Cohen’s 82nd birthday. He isn’t resting easy, though, no matter how well that rest might be deserved. After 49 years (and counting) in the music business, and 13 studio albums to his credit, this anti-crooner and songwriting tour de force is still hard at it. His 14th album, You Want it Darker drops one month from today. He’s been kind enough, though, to share his birthday tidings with us all by releasing the title track, embedded below. It is gravelly gravitas, just like his entire body of work. To honor that retrospective, I’ve also included a wee slice of his older work, including that one gorgeous hymn that’s so often imitated, and so far from duplicated (“I hate that song,” the missus said once as we listened to some anonymous hack mangle it. “Oh but darlin’, you haven’t heard Leonard sing it.”). Enjoy.