A little bit of the seventies died yesterday. Rest in peace, Keith P.

A little bit of the seventies died yesterday. Rest in peace, Keith P.

A little bit of the seventies died yesterday. Rest in peace, Keith P.

A little bit of the seventies died yesterday. Rest in peace, Keith P.

The change in dynamic has been palpable and unstoppable, ever since Harvey Weinstein was outed as a sexual predator. Sure, there’d been naming and shaming before that, with varying level of impacts—Cosby acquitted, Fox News gutted. But the Weinstein story opened the floodgates, with the accusations now coming at us in a fast and furious pace.

The change in dynamic has been palpable and unstoppable, ever since Harvey Weinstein was outed as a sexual predator. Sure, there’d been naming and shaming before that, with varying level of impacts—Cosby acquitted, Fox News gutted. But the Weinstein story opened the floodgates, with the accusations now coming at us in a fast and furious pace.

There’s enough of that in the public realm now that we can begin to categorize it—although doing so risks generalizing incidents that might represent the most objectively awful moments in some victims’ lives. Still, it seems to me, that the behavior reported falls into one of these tiers: criminality (i.e., you belong in jail, and hopefully that’s where you’re headed), dehumanization (you’re accustomed to treating men, women, and children as your personal playthings), disrespect (you’ve treated people with anything less than the dignity, professionalism, and respect that they deserve).

There seems to be a descending hierarchy of gravity there, but that’s nuance, and perhaps, legality. Some of that behavior will land you in jail, some won’t. But make no mistake, it’s all wrong. If you have the slightest moral compass, even if you’ve somehow convinced yourself that you can’t or shouldn’t need to control yourself, you know it’s wrong.

So men (because let us accept this fact: the overwhelming majority of perpetrators we’re talking about are men), if you’ve crossed any of those lines, at any point in your life, you know you did it, and you know it was wrong.

Those living the very public lives, celebrities and the like, who are guilty but not yet named-and-shamed, must be sweating bullets right about now. Because they also very well see that the floodgates are open, and that their time in the pillory is surely just around the bend.

But here’s the thing that implies this momentum can change all of society, not just Hollywood: You don’t have to be a celebrity to be a scumbag. There are a lot more faceless, everyday harassers and abusers among the general population, than there will ever be publicly shamed within the pages of The New Yorker.

That doesn’t mean the shame isn’t coming. The tide is turning—it has turned—and we won’t be getting away with neanderthal behavior much longer.

I said we. I am guilty of treating female colleagues with less than the level of dignity, professionalism, and respect that they deserve.

I’m not writing this to purge myself of culpability, or to make it about me in any way. So I won’t go into a lot of details, other than to say that the behavior I’m admitting to was decades ago—I’ve changed somewhat since becoming a husband and father. I also don’t think it ever rose to the levels of criminality.

None of that excuses anything, though. Because, just like every man who acts this way, I knew I was doing wrong. I did it anyway. How can there possibly be an excuse for that?

I say, therefore, that this is on us, we who act wrongly, have acted wrongly, who condone such acts, who stand idly by while it happens to others. If we’re guilty we’ll carry that load forever; we cannot change what we’ve done. But we can now begin to be agents of positive change.

Start with your own admission, to yourself if no one else. If you’ve done wrong, you know it; you need to dredge that guilt up to the light of day and examine it, probably for your very first time. Recognize what you’ve done, make amends, never do it again.

But don’t stop there, because this thing seems to have a generational life of its own. No male mentor ever told you not to act like a jackass? Well yes, you shouldn’t have needed to be told that, but don’t let that stop you from breaking the cycle. Tell your sons, tell the young men who admire and respect you: Do not act this way. Treat your co-workers, treat everyone, with dignity and respect.

No one deserves to be treated with anything less. Those of us who’ve crossed the line, we knew that, but somehow it wasn’t enough to stop us. But now we can be sure that real consequences are coming: unemployment, public disgrace, jail time. If we can’t change our ways, and we can’t make others change theirs, then this will be the very least that we deserve.

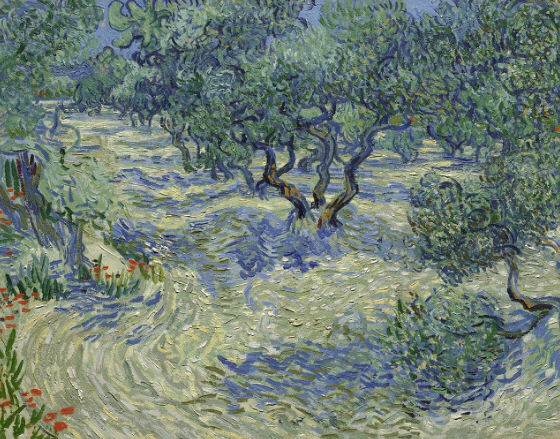

Call it a hazard of painting plein air (or maybe call it, “stilled life”). Vincent Van Gogh, mostly known for his sweetly tragic tenure, is nearly as celebrated for his extraordinary oil-painting technique and masterful interpretation of nature. Like the majority of his landscapes, Olive Trees (1889) was created outdoors, in the elements, amidst the artist’s inspiration. That setting, along with Van Gogh’s habit of deeply layering whorls of paint, has produced a 128-year-old surprise.

Call it a hazard of painting plein air (or maybe call it, “stilled life”). Vincent Van Gogh, mostly known for his sweetly tragic tenure, is nearly as celebrated for his extraordinary oil-painting technique and masterful interpretation of nature. Like the majority of his landscapes, Olive Trees (1889) was created outdoors, in the elements, amidst the artist’s inspiration. That setting, along with Van Gogh’s habit of deeply layering whorls of paint, has produced a 128-year-old surprise.

During recent study to update the artwork’s catalog entry, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which has owned Olive Trees since 1932, discovered the remains of a small, very dead grasshopper locked within the oil paint in the lower foreground. The carcass is essentially microscopic, and is not visible to the naked eye.

During recent study to update the artwork’s catalog entry, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which has owned Olive Trees since 1932, discovered the remains of a small, very dead grasshopper locked within the oil paint in the lower foreground. The carcass is essentially microscopic, and is not visible to the naked eye.

Curators contacted investigative entomologists, in hopes that examination of the insect might offer insight into Van Gogh’s process, and perhaps might identify the season in which Olive Trees was painted.

Unfortunately little could be discerned—the thorax and abdomen of the grasshopper are missing, complicating species identification. The experts did note that the surrounding paint did not seem to be disturbed, suggesting that the grasshopper was already dead when it landed on the canvas. Most likely it was wind-borne.

Interestingly, this was a phenomenon that Van Gogh seemed to be familiar with. In a letter to his brother, penned a few years before the creation of Olive Trees, he wrote, “…I must have picked up a good hundred flies and more off the four canvases you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand…”.

So is there a lesson to be learned from this well-traveled bug’s misadventure, or is it merely an art-history curiosity? Hard to say. Maybe it simply presents an apt metaphor: Do you yearn to learn more about Van Gogh, about painting, about art, about life? Then all you need to do is take a closer look.

‘

‘

It’s rainy and cool here in Deconstruction Central; seasons are changing and the wheel of the year is looping back to its wintry starting point. It is a time of adjustments.

And how we adjust, the process of adjusting, couldn’t possibly be more personal. It’s a puzzle we all must solve, each in our own way.

Another purely personal process, and a related one, is that of creation. Let us all create, and let us all do it our very own way. I cannot think of a better time to engage in creation—it can’t help but to ease this path we’re on, and to help us face these changes with clearer minds and somewhat less burdened souls.

With that in mind, let’s give a hearty thanks to artist extraordinaire Samantha Schumaker for this glimpse into her process. May she help light the spark of our own creative fires….

Let’s begin with what we know: Pierre-August Renoir completed “Two Sisters (On the Terrace)” in 1881. He made no copies.

Let’s begin with what we know: Pierre-August Renoir completed “Two Sisters (On the Terrace)” in 1881. He made no copies.

We know that, in the present day, two separate entities claim they own this original Renoir masterpiece. One is the Art Institute of Chicago. The other is the president of the United States.

The Chicago Sisters has hung in the gallery since it was donated in 1933 by Annie Swan Coburn. Coburn purchased it in 1925 from dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who in turn had purchased it directly from the artist upon its completion in 1881, for 1,500 francs (source).

The version that hangs in Trump Tower may or may not boast such bulletproof provenance. Trump isn’t saying. He insists that his is the original Sisters (he is in fact said to boast often about owning an original Renoir) but declines to share any particulars of its purchase or its history.

We’ve explored in this space often the fraud and deceit that’s endemic to the art world. Well-meaning patrons, cognoscenti, even world-class institutions can and do get taken by talented forgers far more often than most of them would care to admit. Both claimants to the ownership of “Two Sisters (On the Terrace)” would likely be embarrassed should it be revealed theirs was a fake. We can only speculate which would be more averse to embarrassment—and what lengths they might go to avoid such an admission.

To date Trump has resisted all suggestions regarding unbiased authentication of his Renoir, continuing to simply insist that it’s the original. He’s content, evidently, that his word alone should settle the matter.

And so in lieu of employment of the scientific method, we can only once again turn to what we know, and let Occam’s Razor do the rest. Who is more credible, Trump or the AIC? Which is more likely to admit a mistake? Which of them seem most likely to stick to their version of the story, no matter where the facts lead us?

It could very well be that Trump owns the original Renoir, and that the Art Institute of Chicago has been and continues to be snookered. But that’s hardly the point. The point, the overarching lesson—and it’s one that has implications far, far beyond the art world—is that Donald J. Trump has so thoroughly destroyed his own credibility, through his own actions, his personality, and his pathologies, that the razor wielded by Occam pretty much insists to us that Trump is lying. Every time, all the time.

Our own American pathology includes this defensive tic: All politicians lie. It’s one of the ways we force ourselves to accept that which should be completely unacceptable.

But here we’ve gone through the looking glass—here we have a elected specimen that lies so often, reflexively and in the face of easily proven opposing evidence, that we have to assume he lies with every word. If Trump tells you it’s sunny, do yourself a solid and grab an umbrella.

And his Renoir? I’ll be prepared to believe it’s genuine only on the day he publicly declares it a fake.

The Air of the sea,

said the heir of the sea–

burrows its way in your bones.

r

It whispers a plea

one of gilt mystery

and of seeding the depths with unknowns.

r

The heir of the sea

took us there to the sea–

took us there where the tide meets the land.

r

He spoke then to me

of things yet to be

and of things bound be↓ow in the the sand.

r

The fear of the sea

brought the heir of the sea

a league or more u↑p from the coast.

r

He thought he was free

thought the sea would agree

but the sea fears his freedom the most.

r

The heir of the sea

stopped hearing the sea

stopped hearing its thunder & waves.

r

If silence would be

the new voice of the sea

then she’ll speak never more of her graves.

r

Take good care of the sea,

said the heir of the sea–

take care and show her your grit.

r

From her storms never flee

let her eyes never see

all the shadows you’d rather forget.

r

To be dear to the sea

slay the heir of the sea

stay his hand before it raises again.

r

Do it near to the sea

while the wind blows alee

while the waves rush to take him back in.

r

I saw the heir of the sea

stop to stare at the sea

he stopped staring when the sight left his eyes.

r

I thought I might then flee

but he passed me the key–

and I knew then the depths of his lies.

r

This affair with the sea

- said the heir of the sea -

is really quite more than I’ll bear.

r

I’m leaving, said he

he left the sea’s LOVE to me.

And the sea and I birthed a new heir ⏳

It’s hard to say wherein lies the headline here: Is it that a 40-foot tall architectural sculpture can be so unexpectedly suggestive? Or that any sculpture can be suggestive enough to be banned by the Louvre?

It’s hard to say wherein lies the headline here: Is it that a 40-foot tall architectural sculpture can be so unexpectedly suggestive? Or that any sculpture can be suggestive enough to be banned by the Louvre?

Domestikator by the Dutch design collective Atelier Van Lieshout had already been installed in Paris’s Tuileries Gardens, an outdoor annex of the Louvre Museum, as part of an upcoming public-art exhibition, when the museum seemingly had second thoughts. Perhaps they just hadn’t looked at it carefully enough until then? Louvre president Jean-Luc Martinez said, “It risks being misunderstood by visitors to the garden.” Martinez ordered the installation dismantled and removed.

The risk of misinterpretation haunts every creative endeavor—artists, writers, and performers seem to understand this instinctively. The most sanguine among them make their peace with it by accepting that it’s entirely beyond their control. Interpretation belongs to the audience; if they’re perceiving something the artist never intended then maybe it’s less a case of misunderstanding, than one of spontaneous collaboration in creating something new.

As for Domestikator, the eyes are unlikely to lie. Yes, you really are seeing anthropomorphized architecture going where no building materials have gone before. But what does it mean? Its creator-collective might argue that it’s a statement on the post-modern landscape…that our use of technology isn’t just altering the world, it’s crudely dominating it.

Other interpretations are surely just as valid, as are opinions about its worth and worthiness. If you don’t like it, don’t want to look at it, don’t understand why anyone would—you have engaged, and you’re starting a conversation thoroughly worth having.

But not now, not anymore. The Louvre has narrowed our conversation and engagement, leaving us only to talk about something that should have been settled generations ago: censorship. The Louvre censors art; there’s your headline. Even if it’s one almost too dismal to write.

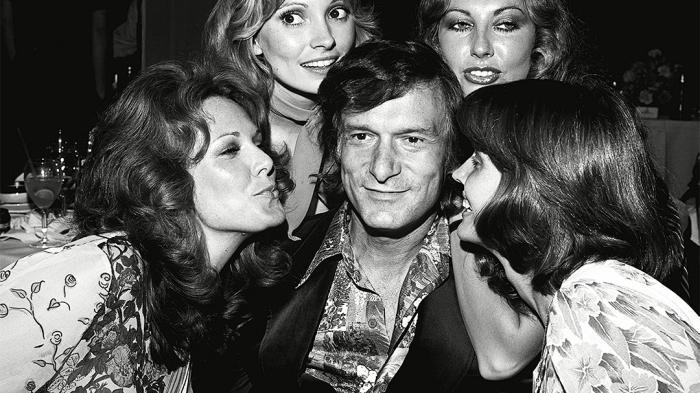

Opinions may vary and we might disagree as to the scope of his contributions, but it’s hard to argue that Hugh Hefner, founder of the Playboy empire (he launched the magazine in 1953 with a borrowed $1000 investment) wasn’t a prime mover of post-war American culture. And we can argue as well whether Hef and his magazine and his mansion full of bunnies were a positive or negative cultural influence…but there’s one vital fact that should play into any such calculation:

Opinions may vary and we might disagree as to the scope of his contributions, but it’s hard to argue that Hugh Hefner, founder of the Playboy empire (he launched the magazine in 1953 with a borrowed $1000 investment) wasn’t a prime mover of post-war American culture. And we can argue as well whether Hef and his magazine and his mansion full of bunnies were a positive or negative cultural influence…but there’s one vital fact that should play into any such calculation:

It was never just about sex.

What Hef created was a rare mixture of hedonism and erudition, of measured thought and base instinct. He sought to both elevate the every-man and every-woman to a higher state of refinement, while acknowledging—even honoring—the fact that they are and always will be creatures of the flesh. It’s a formula that never should have worked, yet it did. It works quite well.

Whether or not Hef was, or should have been, a role model is another point of contention. But if he was, let me posit that in death he offered up one last exemplar of a Playboy’s existence: he left us at a ripe old age, quietly, within the Beverly Hills mansion that’s been his own architectural synonym for decades.

So love him or hate him, let’s respectfully bid him goodbye. Goodnight, sweet Hef. May warrens of bunnies sing thee to thy rest.

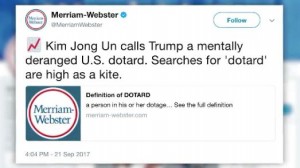

The office of Dear Leader of the DPRK is traditionally endowed with a lot of not-especially useful superpowers (all three of them were apparently adept at finishing up golf outings with 18 hole-in-ones)…but not even the most loyal and/or terrified North Korean could have predicted that wee rolly polly Kim Jong-un could have out-flash-memed the Trumpster on his own virtual turf. Such a bizarre development could indeed suggest he just might not be the man they think he is at home. Oh no no no.

Because love him, hate him, fear him, and/or mock him, the rocket man in the platform shoes wins this round decisively, while the larger campaign of pre-nuclear dick-measuring rages on. He and Trump squared off, eyed each other, and launched tactical nicknames. Trump’s attempt probably sounded good in his head, but all he did was put an awfully enjoyable song in all of ours. But when Kim that magnificent bastard returned fire, he sent half the English-speaking world scrambling for dictionaries.

Dotard. He called him a dotard. Donald J. Trump please click here for a directory of reputable burn clinics near you.

Our conundrum is this: no matter how you feel about Trump, if you have a spark of human dignity in you, you never ever want Kim Jong-un to be right about anything, ever. But then he goes and calls Trump a dotard, and either you looked it up or you already knew what it meant (sure you did), and then you sat and thought about it. Trump. Dotard. Dotard-Trump.

Our conundrum is this: no matter how you feel about Trump, if you have a spark of human dignity in you, you never ever want Kim Jong-un to be right about anything, ever. But then he goes and calls Trump a dotard, and either you looked it up or you already knew what it meant (sure you did), and then you sat and thought about it. Trump. Dotard. Dotard-Trump.

Uncanny, Kim. Uncannily on the nose.

You have to dig deep for it, but there’s a glimmer of hope in all this. Kim wins the internet, so we laugh. Laughter is unexpected yet so so welcome in the midst of intercontinental tandem temper tantrums. That pair of man-children both salivate over the idea of a war that neither will have to fight, but as long as they’re hurling names, just names, maybe we can enjoy a laugh or two before the dotard and the rocket man kick things up a notch or ten.

Or it could be better even than that. Neither of them shows any sign of being easily deterrable, but both give every sign that they loathe being laughed at. The opportunity is ripe—they’re acting like clowns after all. So let’s laugh at them and see where that takes us.

I can see a future where both are laughed from power: Trump free to schlump further into his dotage, and Kim eagerly sought after for Hollywood parties, where he exhibits his limitless skill in summoning the perfect obscure OED ephemera to hand out as nicknames. Dennis Rodman emcees.

You never know, and it’s never too late to hope, and it should never be too grim to laugh. So give it a try. Just laugh at those twits.

First though, we’re gonna need a funnier name than Rocket Man. Thanks, dotard.

Hey. I’m a little worried about you. I think you need to take a breath.

Hey. I’m a little worried about you. I think you need to take a breath.

I know you hear that a lot. Someone’s always telling you that, or versions of that. Chill down, chillax, get your bloomers out of their uproar. Fifteen thousand curveballs and fastballs life’s been throwing at you, big ones and small ones and ones that seem like they’ll shake apart the universe.

It’s enough to make you lose your breath.

And that’s one solution I suppose. You can overrule the autonomic til you turn blue. Stamp your foot. Shut your eyes and shake your head. Or you can breathe.

Just breathe. Slowly, to a count of four, thinking about nothing except breathing. Pull in your breath with your abdomen, use your muscles, fill your lungs for four beats. Hold for a tic. Breathe out four beats.

Then do it again.

Whatever life you are going to live, whatever fate has in store for you, your time here is going to be bookended by breaths. You drew your first one upon arrival, you’ll let out your last just as you leave.

And whatever life you live, you’ll always share a few common features with the flame: it needs to breathe just as badly as you do. It consumes, it propagates, but it’s going to sputter. Best it can do is leave some kind of mark before it goes.

How bright you burn, and whatever makes you burn, and whatever you do next is something only you can determine. Be a candleflame or conflagration. Either way, make your mark

Just take a breath first. Relax when you do. Draw in the air slowly, let it out slowly, and push away all other considerations. Just for a while.

Then go ahead and get busy immediately thereafter. You’ve got plenty to do, and there’s plenty that needs doing. You’ll lose yourself in that maelstrom, in what’ll seem like mere seconds. You shouldn’t fash yourself, it happens to us all. We all get swept back in. And we stay there, turning and churning—

until we remember to take a breath.

(P.S., if you need a little more of the same, try this.)

It’s probably the right thing, the duly deferential thing, to observe Labor Day (America’s tempered version of May Day) by reflecting on the successes and legacies of the U.S. labor movement. The forty-hour workweek, job-safety regulations, even this very holiday itself were all created by, for, and likely wouldn’t have been conceived without a thriving American labor class.

It’s probably the right thing, the duly deferential thing, to observe Labor Day (America’s tempered version of May Day) by reflecting on the successes and legacies of the U.S. labor movement. The forty-hour workweek, job-safety regulations, even this very holiday itself were all created by, for, and likely wouldn’t have been conceived without a thriving American labor class.

But it’s hard to resist, in the course of these Labor Day reveries, not reflecting also on the contemporary state—the current muscle—of American labor. It has atrophied, it is on the wane, and it is on the run. Even as wages stagnate and union rolls shrink, an ascendant conservative polity, hostile as ever to organized labor, wages a multi-front campaign against the movement. State by state, unions’ reach and scope are being legislatively eroded, while in the marketplace of ideas, the right-wing canon preaches an anti-labor gospel that has been frighteningly effective in shaping the opinion of socially conservative, low-wage workers—ones with arguably the most to gain from a strong, vibrant labor movement.

It’s a chronic condition, even if it’s feeling particularly acute. Labor’s back has been up against the wall for well more than a generation now. And since it’s clear that the counterpunches thrown thus far have, at the wildly optimistically best, only somewhat slowed the trend, I’d argue it’s time to rethink strategy.

Fortunately, conditions have aligned themselves in support of just such a shift. We’re seeing a completely organic grassroots resistance movement, independent of party politics, spring up in resistance to the hostile, unstable, cryptofascistic national leadership, and the cronies and hangers-on that support it. This movement is vibrant, growing, effective, and as yet hasn’t been co-opted by any of the usual political suspects, who could be counted on to turn it into just another exploitable constituency. Here’s hoping it stays that way.

Labor very much has a role to play in this phenomenon—probably multiple roles, in fact. And while it can be, should be, incumbent upon every union, local, and individual worker to formulate for themselves how they can best dovetail with the resistance already underway, I humbly put forth my suggestion for a strong, nation-wide Blue-Green coalition.

The concept is deceptively simple: a synergistic alliance  of organized labor and environmental activists. Common ground between them is more evident than ever before—high-paying green-tech industry jobs now outnumber those in the fossil-fuel extraction sector, while a focus on fair trade is understood to be protective of both jobs and the environment.

of organized labor and environmental activists. Common ground between them is more evident than ever before—high-paying green-tech industry jobs now outnumber those in the fossil-fuel extraction sector, while a focus on fair trade is understood to be protective of both jobs and the environment.

But there are, of course, areas of disagreement. Most recently, unions and environmental groups clashed over projects like the Keystone Pipeline—that very disagreement led to the breakup of at least one blue-green coalition. As more such projects move forward, this friction is sure to increase.

The answer is to view the alliance with the tactical urgency it deserves. Alliances under fire are never perfect, but the immediacy of their struggle necessitates working around, even temporarily tabling areas of non-alignment.

And make no mistake—this is precisely that urgent. Climate change is a looming existential threat. American leadership, even engagement on the issue has been abrogated. The vacuum after Paris has left not just an opportunity for groups like organized labor and environmental advocates to seize relevancy, but an absolute obligation for them to do so.

Our labor movement has, at its core, always been about preserving and protecting the future of the voiceless multitude. It pools its strength and its industrial clout not to seize the means of production, as Marx proclaims and conservatives believe, but to turn those means into a more fair pillar of modern society. That clout might have been diminished but it’s never disappeared. And the time is right, right now, to apply it to a cause that doesn’t just serve labor, but potentially saves us all. Happy Labor Day.

Well no, not really. It’s really just a convergence of events: haven’t posted in a while but don’t yet have the energy to take on the drowning of Houston or the marching of nazis or the deep foul bucket of other pressing current events. Plus I have in my possession some interesting graveyard snaps to share with you. Plus I have in my possession a couple pieces o’ poesy that more or less take place in graveyards. Since they gel with the aforementioned then they also I aim to share with you. We’ll circle back another time to current events fair and foul, and arts & culture most definitely fair. The verse is only an interlude, and at times an unwelcome but still needful reminder of those rotten things to which fate binds us…

Everyone’s Speeding to the Same Destination

Everyone’s Speeding to the Same Destination

Boneyard requiem, that final wormy dance

from birth to death, cradle to grave

poor bastard never stood a chance.

From embalmed flesh to forgotten dust—coffin nails long turned to rust

until

No one living recalls his name

He might not have ever been.

.

.

Late Embrace

I waited five weeks to find where she lay - embraced by the soil, wrapped in decay. - Every turn of my spade was wrought by my heart. No terrestrial boundaries could keep us apart.

The world scorned my yearnings, labeled me mad. I sought her sweet favors, her family forbad. Some fever then took her, it stole her from me. But the black veil of sorrow would ere set us free.

When my spade finally found her I sobbed my delight. I seized her, embraced her, and dragged her toward light. Did anyone see us? I never did care; there by her graveside our love laid us bare.

Our union was perfect, a coda to woe: I wouldn’t be sated, she couldn’t say no. We stayed there together til the rise of the moon, then I kissed her and told her to expect me back soon.

We were lucky to live, for as long as it lasted, in a world co-inhabited by Jerry Lewis. That funny, funny man lived to the most venerable age of 91, and he died at home—these are blessings by anyone’s measure. But tomorrow the sun will be blotted from the sky and it might as well stay that way, because tomorrow begins the age without Jerry. I think laughter itself died today.

We were lucky to live, for as long as it lasted, in a world co-inhabited by Jerry Lewis. That funny, funny man lived to the most venerable age of 91, and he died at home—these are blessings by anyone’s measure. But tomorrow the sun will be blotted from the sky and it might as well stay that way, because tomorrow begins the age without Jerry. I think laughter itself died today.

I know not everyone feels this way. Not everyone thought he was as funny as I do. But there, again, is the blessings of the existence of this extraordinarily complex man—if he failed you as a comedian you might be duly impressed by his turns as a dramatic actor (The King of Comedy with De Niro in 1982, as well as the highly underrated Funny Bones in 1995). Or, quite notably, his unrivaled humanitarianism; he hosted the Muscular Dystrophy Association telethon for an astonishing 45 years. Generations of desperately ill children have been known, probably always will be known, as Jerry’s Kids.

Or, if nothing, else, just let yourself appreciate his distinction as a true and selfless friend. That’s been a common refrain in the memoirs and public statements of those who knew him. But you could see it for yourself, plainly and hauntingly, during the live-aired reunion between he and Dean Martin during the 1976 MDA telethon. It was palpable. Business and artistic differences had split them apart but they still cared as deeply for each other as two human beings were able. They remained close until Martin’s death in 1995.

Or, if nothing, else, just let yourself appreciate his distinction as a true and selfless friend. That’s been a common refrain in the memoirs and public statements of those who knew him. But you could see it for yourself, plainly and hauntingly, during the live-aired reunion between he and Dean Martin during the 1976 MDA telethon. It was palpable. Business and artistic differences had split them apart but they still cared as deeply for each other as two human beings were able. They remained close until Martin’s death in 1995.

And still he soldiered on. Ages removed from his biggest commercial successes in the late 1950s and early ’60s, he kept acting, writing, and directing well into his twilight years. Ill health hardly slowed him down. He suffered through prostate cancer and a pair of heart attacks, and kept on working, long past the point where lesser men would retire. He was on stage and in his zone as recently as last year.

His rest, then, is most well deserved and it is only through our fondness and grief that we regret his passing. It is through our memories that we celebrate all that came before.

My city, Akron, boasts a myriad of ways to deliver art and culture to we, her lucky citizens. Our local arts scene is thriving beyond all proportion to our size, geography, and, I’d guess, our reputation. Much of that is a grassroots phenomenon, driven by people like my own better half—embedded artists doing much more than their own fair share to serve us all by serving up the arts.

My city, Akron, boasts a myriad of ways to deliver art and culture to we, her lucky citizens. Our local arts scene is thriving beyond all proportion to our size, geography, and, I’d guess, our reputation. Much of that is a grassroots phenomenon, driven by people like my own better half—embedded artists doing much more than their own fair share to serve us all by serving up the arts.

But due credit must go to the municipality as well, which puts as much effort into that same noble cause that some towns devote to rib fests and hot-dog eating contests (not that there’s anything wrong with either of those). The city’s summertime Dance Festival is one example among many, but it’s at top of mind for me at least as I’ve spent the last two consecutive Fridays taking in the dance performances that my city has worked so hard to bring before me.

These weren’t my first such exposures—a couple years ago I reported on my attendance at a truly stunning performance by Ballet Hispanico. It was transformative; at the time I noted that dance was (and is) a performing art about which I know little, and with which I’m least engaged. Yet I saw something there—felt it—that let me know that here was an art with depth and breadth of meaning, of subtext, of storytelling.

I felt that again, I confirmed it, these past two weeks, with outdoor, under-the-blazing-stars performances by Groundworks DanceTheater and Urban Bush Women. Their styles, approaches, methods, and stories are vastly different, and I haven’t the words or aptitude to try to interpret or contrast or even to describe them. All I can say was that in each case, in equal measures, I was rapt, fully pulled in, fully experiencing each nuance of motion.

I felt that again, I confirmed it, these past two weeks, with outdoor, under-the-blazing-stars performances by Groundworks DanceTheater and Urban Bush Women. Their styles, approaches, methods, and stories are vastly different, and I haven’t the words or aptitude to try to interpret or contrast or even to describe them. All I can say was that in each case, in equal measures, I was rapt, fully pulled in, fully experiencing each nuance of motion.

What I hadn’t understood, what I’m still coming to terms with, is that these dancers do very much tell a story; they take the stage in order to encode a message. It is sometimes an anecdote, often an entreaty, not infrequently a desperate demand.

The music that gives fluidity to their movements are elements of story, but—and I suspect this is key—silence is too. There’s something strangely unsettling in seeing a long stretch of choreography unaccompanied by music. The audience becomes supernaturally still, and all that can be heard is the slap and stomp of the dancers’ feet, and the sounds of their exertions. The music goes missing, the dance goes on. There are obvious theses to what they’re telling me from the stage, but there are much more subtle revelations hidden within the nested layers, some of which I’m not entirely sure I was meant to understand. That is a reminder and a constant of life writ large. In dance and in everything, I come to terms with it.

So dance, I say, is cerebral beyond anything I ever suspected or would have posited.

Or…maybe it’s just dance. Let us all be the judge:

We lost one of the good ones today—a superb musician, a star, and a gentleman. There’s solace in knowing he had the time and the ability to tell us all goodbye. But there’s sadness because Alzheimer’s disease is a gold-plated bitch.

We lost one of the good ones today—a superb musician, a star, and a gentleman. There’s solace in knowing he had the time and the ability to tell us all goodbye. But there’s sadness because Alzheimer’s disease is a gold-plated bitch.

Thanks for the music, Mr. Campbell, and goodnight.